Emma Howgill is currently a project archivist at the Theatre Collection, working on the Julia Trevelyan Oman archive. When Emma was project archivist in Special Collections, she completed the cataloguing of Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s S.S. Great Eastern letter-books and here writes about some of the highlights therein.

Earlier this year, Special Collections finished a six-month project to catalogue the six letter-books kept by Isambard Kingdom Brunel during his final project, the S.S. Great Eastern.

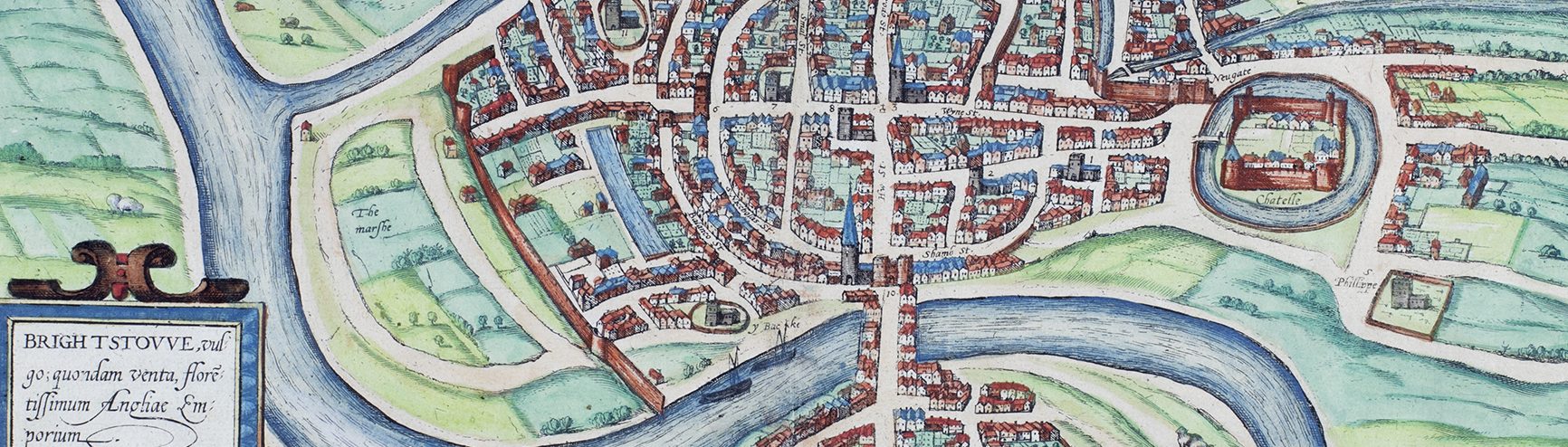

Built over a seven-year period, from 1852 to 1859, the S.S. Great Eastern was Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s last major project; the third and largest of his three great ships. At 692 feet long and 18,000 tons, the S.S. Great Eastern was, for over 40 years, the largest ship built and was only surpassed in both length and tonnage by the great ocean liners of the early twentieth century. Indeed, the ship was so large that she required not only a screw propeller, which Brunel had used with great success on the S.S. Great Britain, but also paddle wheels.

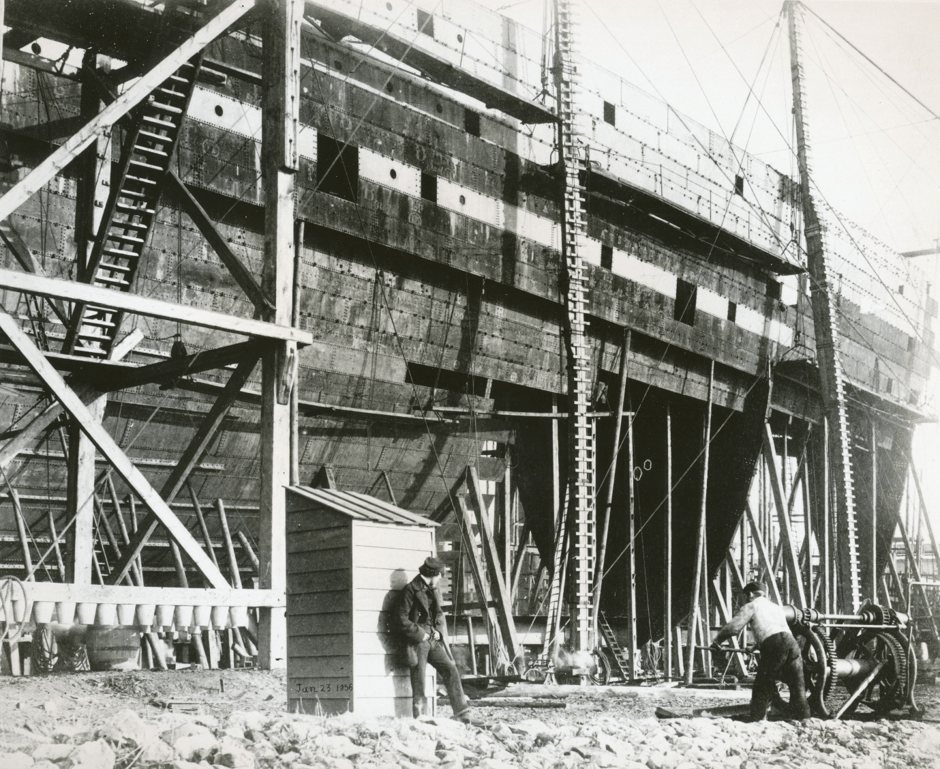

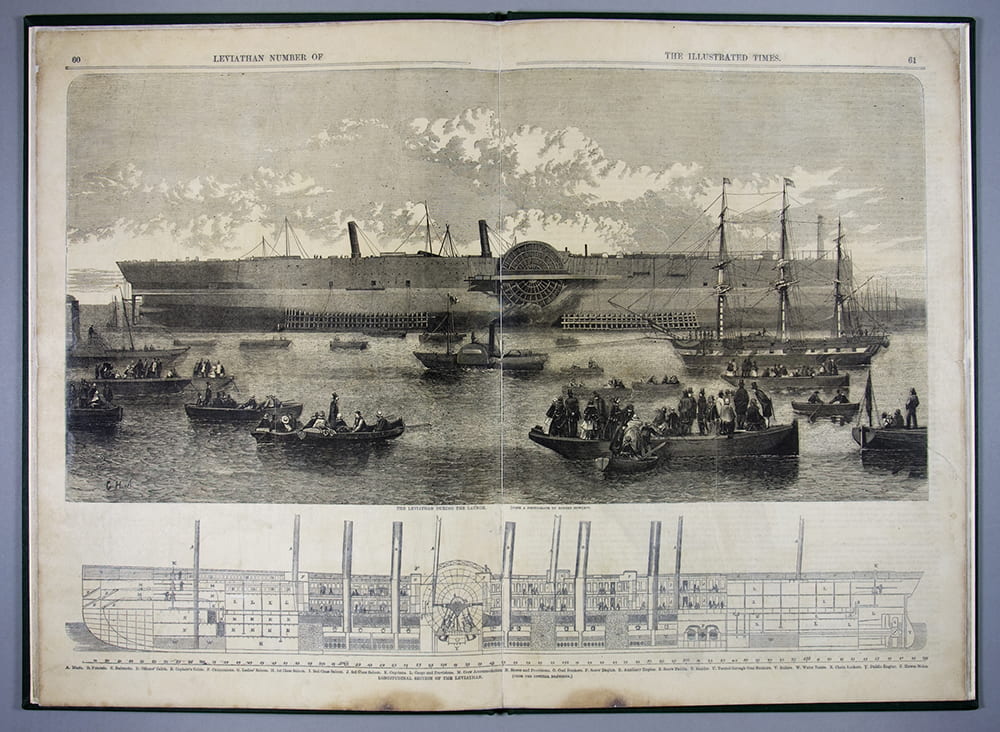

A page from the Leviathan Number of The Illustrated Times, 1858, showing the S.S. Great Eastern under construction in London. DM1378.

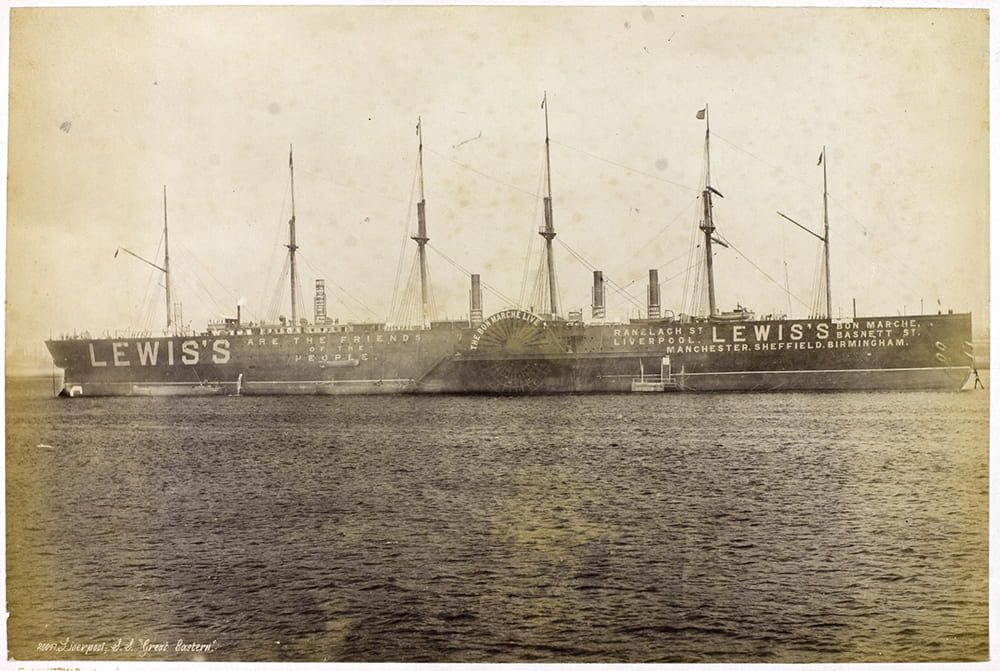

However, the ship was dogged by misfortune throughout her life. Even during construction, the ship suffered misfortune with a disastrous fire in the shipyard and the bankruptcy of ship-builder John Scott Russell. On her maiden voyage around the south coast of England, one of the boilers exploded, blowing off one of the ship’s funnels and fatally injuring several of the stokers. Despite her fame, the ship was not a great success as a passenger ship and she was sold and refitted for the laying of transatlantic telegraph cable. She ended her life moored at Liverpool, where she became a floating billboard for a local department store before being broken up in 1889.

The S.S. Great Eastern, moored in the Mersey, advertising David Lewis’s department stores in Liverpool, Manchester, Sheffield and Birmingham, c.1886-87.

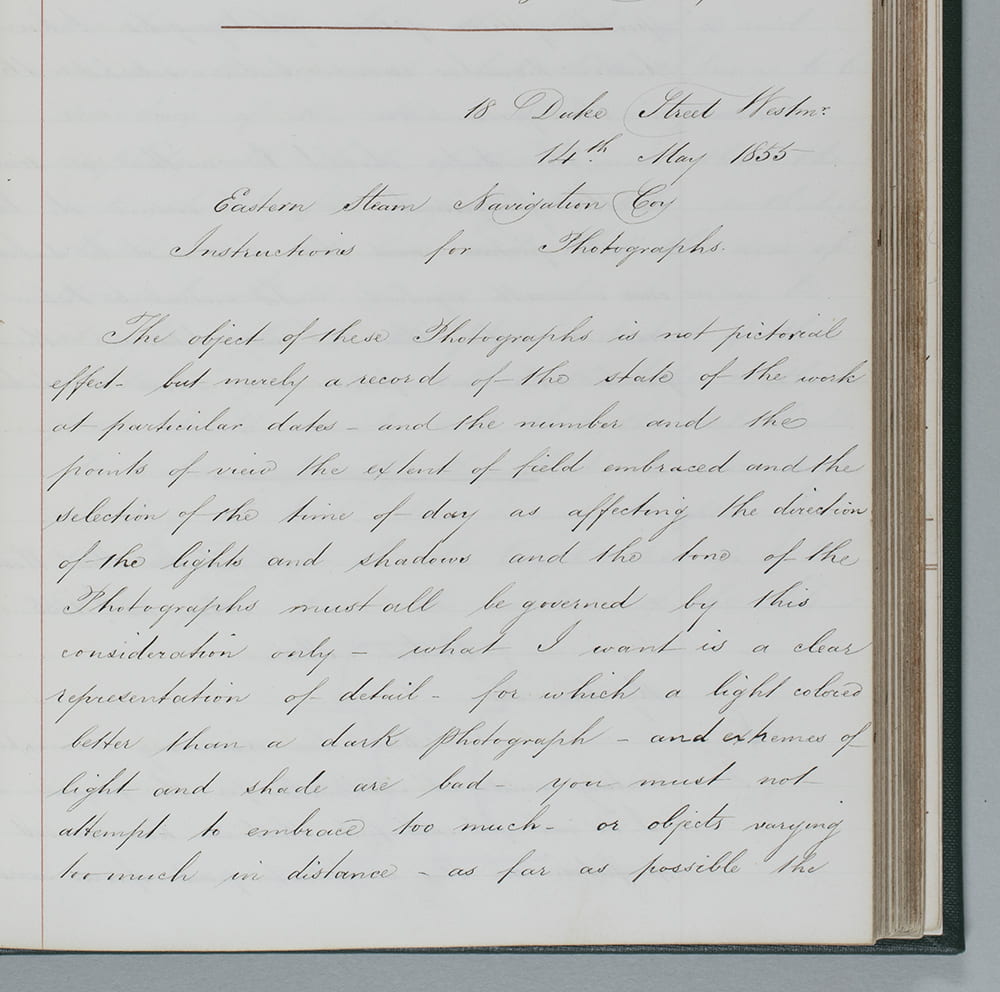

Throughout the construction of the ship, Brunel kept letter-books, six large volumes into which every piece of correspondence sent or received regarding the Great Eastern was copied. These volumes are an amazing resource, effectively detailing the entire progress of the project and illuminating many of Brunel’s thought processes and his relationships with colleagues and suppliers.

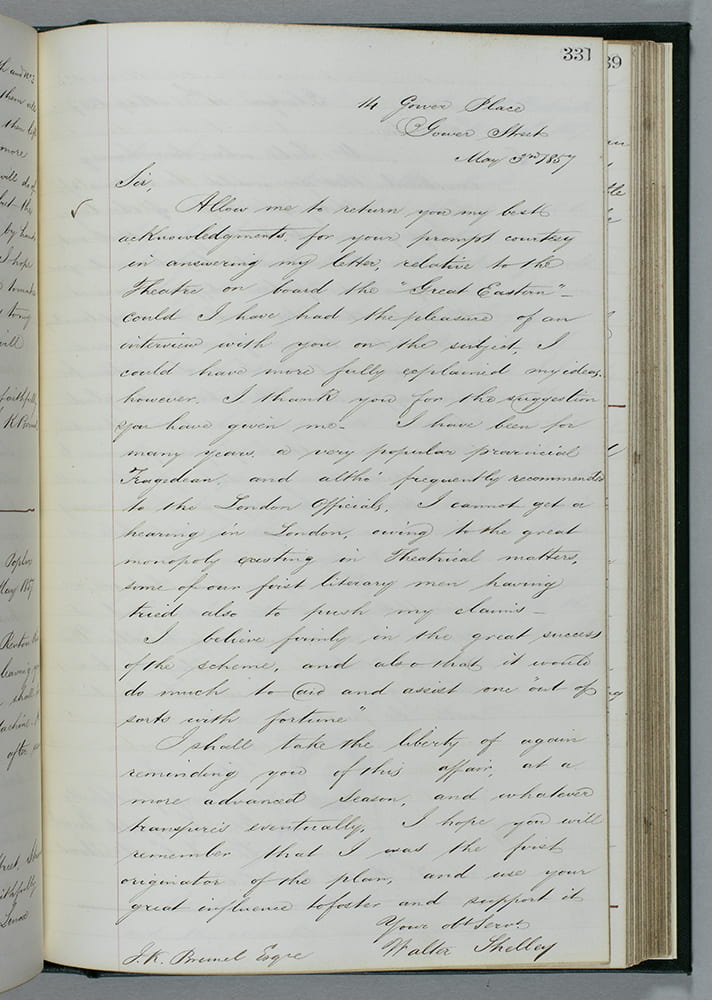

Letter from Walter Shelley to Isambard Kingdom Brunel, suggesting that Brunel might like to include a theatre on board the Great Eastern. 3 May 1857. DM1306/11/1/4/folio 331.

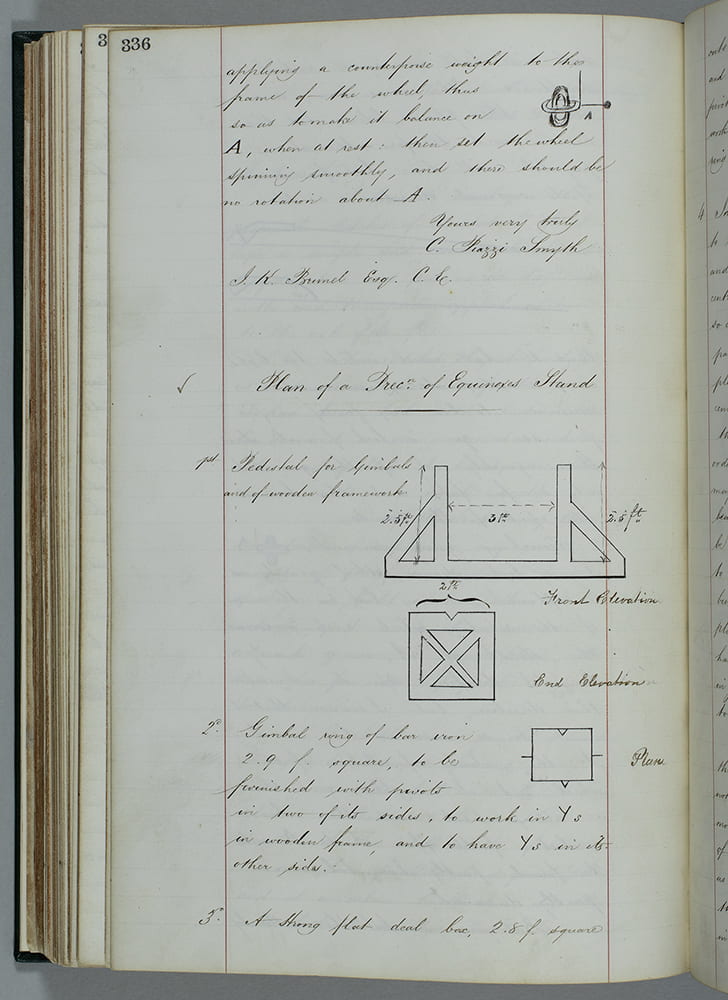

The letter-books reveal not only the grandeur and luxury of the Great Eastern but also her technological innovations. Brunel received several letters from people eager to include a variety of leisure activities onboard for passengers, including a theatre and a library with books specially bound to match the ship’s decorations, as well as a working printing press for passengers to admire. As well as leisure activities, the ship was also full of technological marvels, some devised by Brunel, others by a host of inventors eager to use Brunel’s celebrity to boost their own fame. Brunel himself believed that the unprecedented size and speed of the ship would change methods of navigation and would require new instruments for continuously monitoring the ship’s position. He set about, with the help of Professor Airey of the Royal Observatory, Greenwich and Professor C. Piazzi Smyth of the Royal Observatory, Edinburgh, to devise new navigational instruments. Brunel also invented a device for monitoring sea-water conditions which would sound an alarm when water conditions were favourable for icebergs.

Part of a letter from Professor C. Piazzi Smyth to Isambard Kingdom Brunel, with ideas for a new type of observational instrument stand. 9 December 1854. DM1306/11/1/1/folio 336.

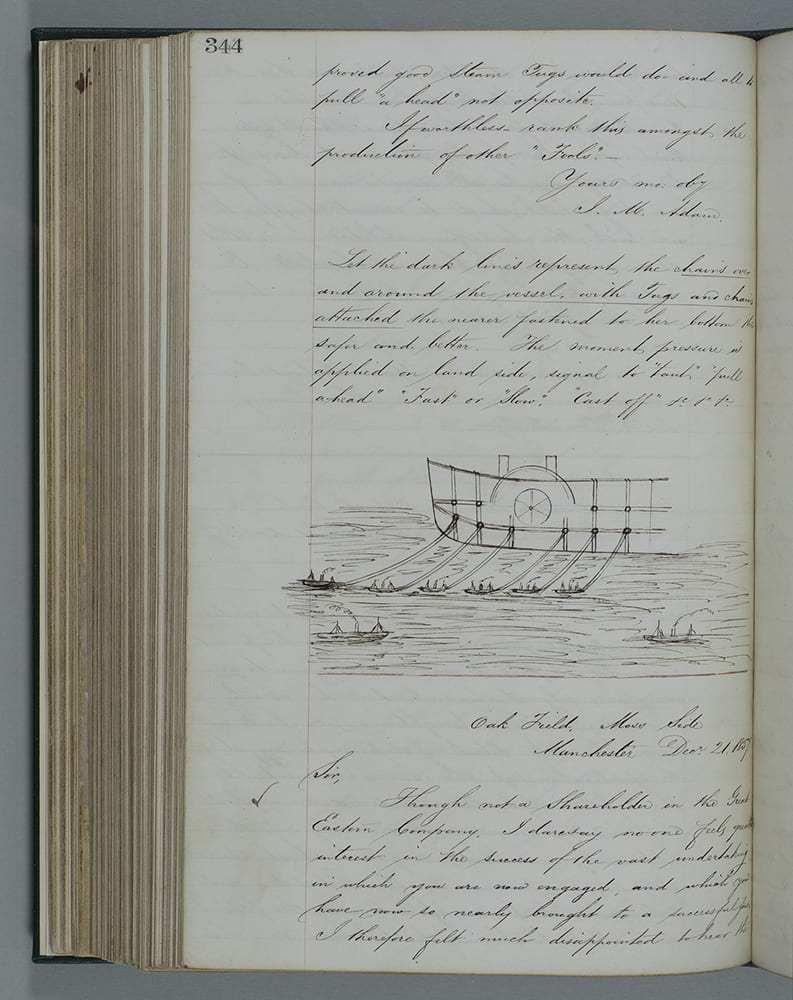

The letter-books also illuminate some of the project’s failures and the great public interest in the project. In June 1856 Brunel wrote an impatient letter to the secretary of the Eastern Steam Navigation Company requesting that public visits to the ship be restricted to the lunch hour since the number of visitors attempting to visit the ship was seriously disrupting the work (DM1306/11/1/3/folio 275). Then, following the first, disastrous, attempt to launch the Great Eastern in December 1857, the letter-books reveal the out-pouring of public opinion and the wealth of suggestions, some helpful, some not so helpful, that were sent to Brunel in the hopes of assisting with the launching of the ship.

Sketch accompanying a letter from I.M. Adam to Isambard Kingdom Brunel, offering suggestions for launching the S.S. Great Eastern. 21 December 1857. DM1306/11/1/5/folio 344.

Cataloguing these six letter-books has uncovered a wealth of detail about the revolutionary but ill-fated S.S. Great Eastern and reveals the attention to detail that Brunel paid to the ship, as well as the great public interest that the ship aroused. We hope that by making a detailed catalogue and high- quality images of the contents of the letter-books available online, we can continue to serve this public interest which still remains, over 160 years after the Great Eastern’s launch.

If you want to explore Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Great Eastern correspondence in more detail, please visit our online catalogue or you can arrange to visit the original letter-books which are held at the Brunel Institute.