Emma Howgill is a project archivist at Special Collections, University of Bristol. She has recently completed the cataloguing of Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s S.S. Great Eastern letter-books.

As a project archivist, my job is full of enjoyable moments and satisfaction. There’s the satisfaction of being one of a privileged few people who get to go through, in painstaking detail, a variety of archives. There’s the joy of getting to know someone who may be long dead, through their own words and personal correspondence and relationships. Then there’s possibly the best part of my job; the thrill of putting disparate bits of information together to make connections. These connections might be between different parts of the same archive, with material in other archives or with knowledge floating around in the back of my brain. While cataloguing Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s correspondence relating to the S.S. Great Eastern (DM1306/11/1), I got to make all three sorts of connections.

The S.S. Great Eastern was Brunel’s last project; the third and largest of his three great ships and was dogged by misfortune throughout her life. From a fire in the shipyard and the bankruptcy of the shipbuilder, John Scott Russell, to the three months that it took to launch the ship and a disastrous explosion that blew up one of the funnels and killed several of the crew during her trial voyage from London to Weymouth, the ship seemed ill-fated. Even once in service, disaster seemed to follow the ship and eventually she was broken up in 1889, having served out her last few years as a floating billboard for a local department store in Liverpool. Yet in engineering terms, the ship was a significant achievement. At 692 feet and over 18,000 tons, the S.S. Great Eastern held the title of the largest ship ever built for over forty years. The ship was also packed with revolutionary engineering techniques; from her double-layered iron hull to a series of bulkheads allowing compartmentalisation of the hull in case of flood or fire. It is no wonder, with such revolutionary size and construction techniques that Isambard Kingdom Brunel wanted his magnum opus to be recorded in detail. And that is where the connections come in.

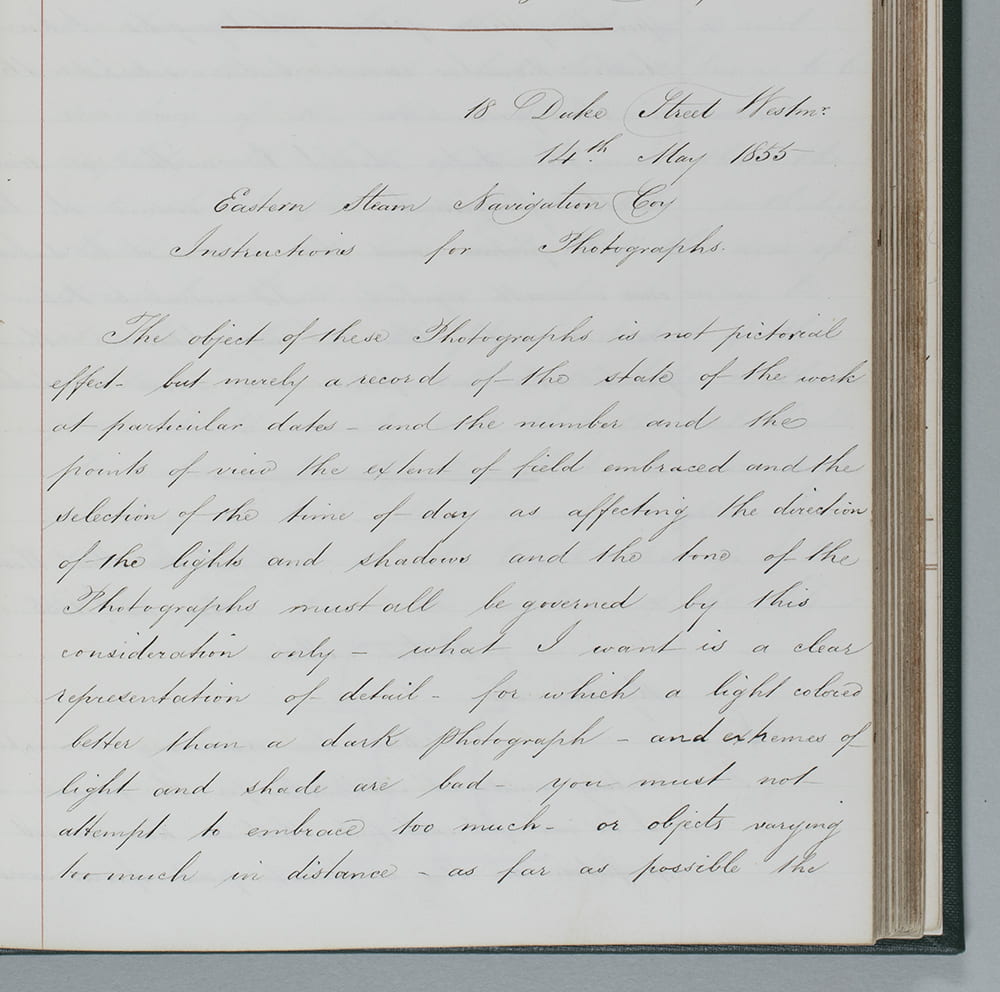

Over a period of six months, I catalogued six volumes of correspondence, covering eight years and countless correspondents on numerous topics. Cataloguing a sequence of correspondence like this allows themes to emerge. In October and November 1854, Brunel and his ship-builder, John Scott Russell, discuss a set of photographs that Brunel wishes to commission of the ship’s construction. This phase of correspondence finishes on 8 November 1854 with a letter from Brunel to John Yates, secretary of the Eastern Steam Navigation Company, mentioning that Brunel has commissioned a regular photographic record be made detailing the progress of the construction of the Great Eastern (DM1306/11/1/1/folio 304-305). Seven months later there is another set of correspondence about these photographs, beginning with a letter from Isambard Kingdom Brunel asking to see the photographs of the Great Eastern under construction (DM1306/11/1/2/folio 72). This set of correspondence ends with two pages of Instructions for Photographs listing exactly how Brunel wants any future photographs to be taken (DM1306/11/1/2/folio 85-86). And just over a year and a half later, on 9 December 1856, there is a letter from Joseph Cundall of the Photographic Institute in New Bond Street, requesting payment for taking these photographs. Brunel’s letter-books, carefully showing the sequence of all the correspondence that he both sent and received about the Great Eastern allows us to trace the development of Brunel’s idea to illustrate the process of constructing his great ship, from its conception to payment.

First of page of Brunel’s Instructions to Photographers, 14 May 1855. DM1306/11/1/2/folio 85-86.

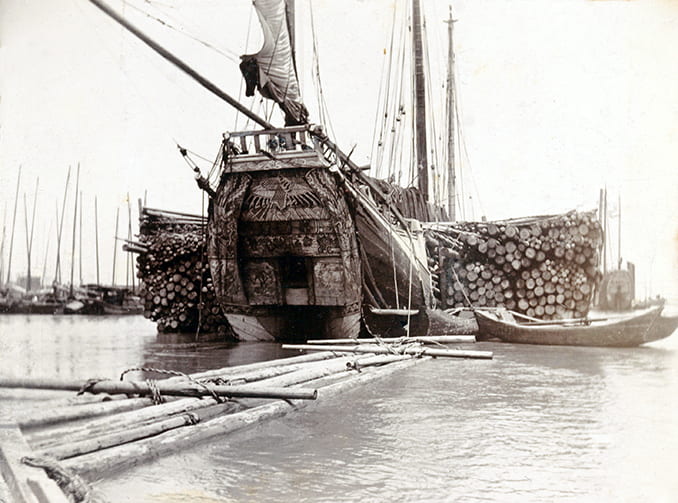

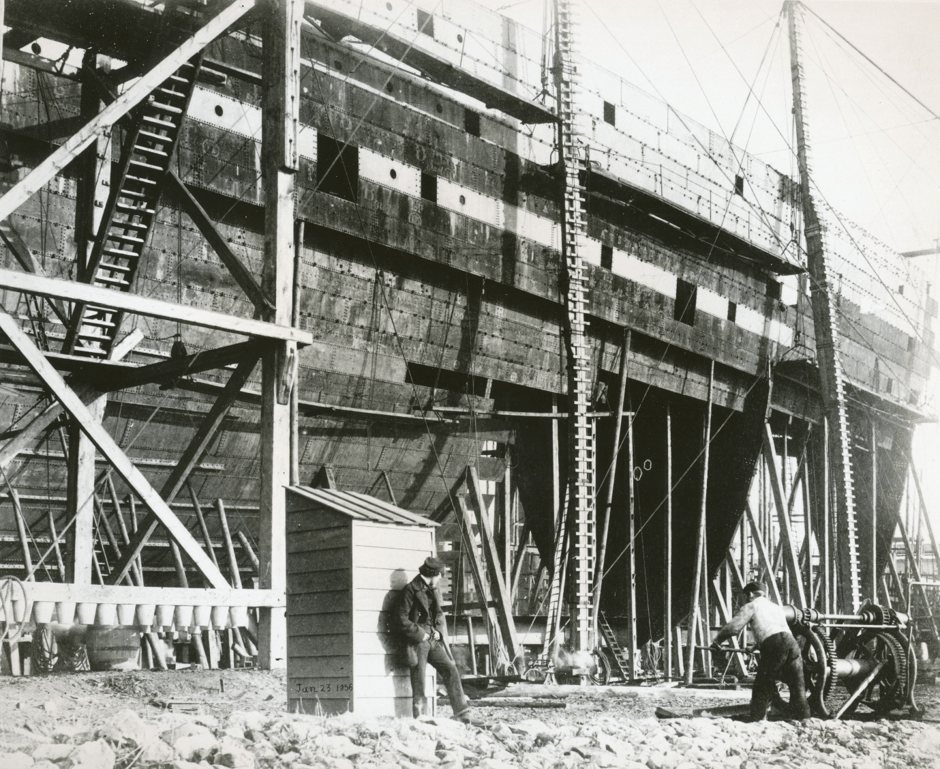

This correspondence also allows us to connect our collections at the University of Bristol with those at the Special Collections of the University of Bath. The Hollingworth collection at the University of Bath contains typed transcripts of correspondence about the construction of the S.S. Great Eastern as well as copies of some photographs of the ship. Close examination of these photographs reveals them to be the ones commissioned by Brunel from Cundall and Howlett, and in fact demonstrates that Brunel’s chosen photographers actually included many of the points made in his Instructions for Photographs of the 14 May 1855 (DM1306/11/1/2/folio 85-86). For example, comparing the photographs shows them to have been taken from several distinct spots around the ship, so that when the photographs are arranged chronologically, it is possible to track the growth of the double-skinned hull across the months by comparing distinct landmarks incorporated in each photograph. This echoes Brunel’s explicit instructions to ensure that the photographs are taken from comparable spots. The images also demonstrate Brunel’s wish to have the date of each photograph somewhere in the image itself, thus allowing quick and easy identification of the rate of progress, and it is possible to engage in a Victorian game of ‘Where’s Wally’, finding the date of each photograph, whether hidden on wooden beams or inscribed on the side of a watchman’s hut.

Photograph taken by Cundall and Howlett showing the S.S. Great Eastern under construction. 23 January 1856. Photograph from the University of Bath Special Collections.

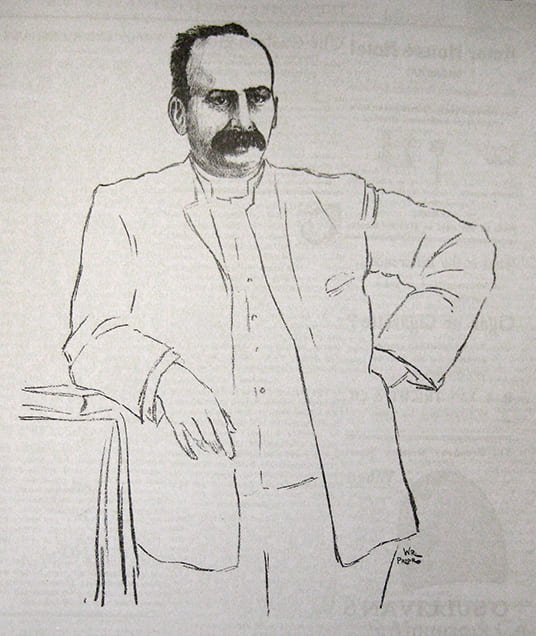

Now come the external connections. Joseph Cundall, the photographer writing to Brunel in December 1856 requesting payment for his work, was the senior partner in the firm of Cundall and Howlett. Cundall himself had earlier been tasked to photograph the rebuilt Crystal Palace with which Isambard Kingdom Brunel was also involved when he helped to design the steam heating system of the new Crystal Palace. Cundall’s junior partner, Robert Howlett, through this Great Eastern commission, was subsequently responsible for what may arguably be one of the most recognisable photographs of the Victorian Age. As well as photographing the construction of the S.S. Great Eastern, Howlett was commissioned by the Illustrated London News to capture the launching of the Great Eastern in November 1857. As part of this later commission, he photographed Isambard Kingdom Brunel standing, with his ubiquitous hat and cigar, in front of the great drums of the launching chains of the Great Eastern, an image that has come to define not only Isambard Kingdom Brunel, but also Victorian engineering. Before Howlett’s untimely death in 1858, he had been commissioned by Prince Albert to photograph some of the interiors of Buckingham Palace and the works of artist Raphael, as well as being commissioned, with Joseph Cundall, to produce photographic portraits of soldiers returning from the Crimean war for Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. And so this one letter from Joseph Cundall forges a series of connections within Brunel’s Great Eastern correspondence, with neighbouring archives but also with two of the early pioneers of photography and with one of the most instantly recognisable photographs of the Victorian age.

If you want to explore Isambard Kingdom Brunel’s Great Eastern correspondence in more detail, please visit our online catalogue, or you can arrange to visit the original letter-books which are held at the Brunel Institute.