Karl Offen is Professor of Geography and the Environment at Syracuse University in New York. He specializes in the historical geography of Central America and the Caribbean. Caroline A. Williams (1962-2019) contributed in absentia to this post. Caroline was a professor in The Department of Hispanic, Portuguese and Latin American Studies at the University of Bristol until her untimely passing. An article about her many and diverse scholarly achievements can be accessed here. As much as I would like to say that Caroline co-authored this post, I must acknowledge that she did not and that any errors are mine alone.

‘Prepare to be amazed!’ This was how Caroline started an email to me in 2014. She had just received transcriptions of some 30 family letters of a private collection that we had been searching for. ‘There is so much information, I’m at a loss for words’. The email could not contain her elation, and after reading the rest of her message I too understood that we had stumbled upon a once in a lifetime find.

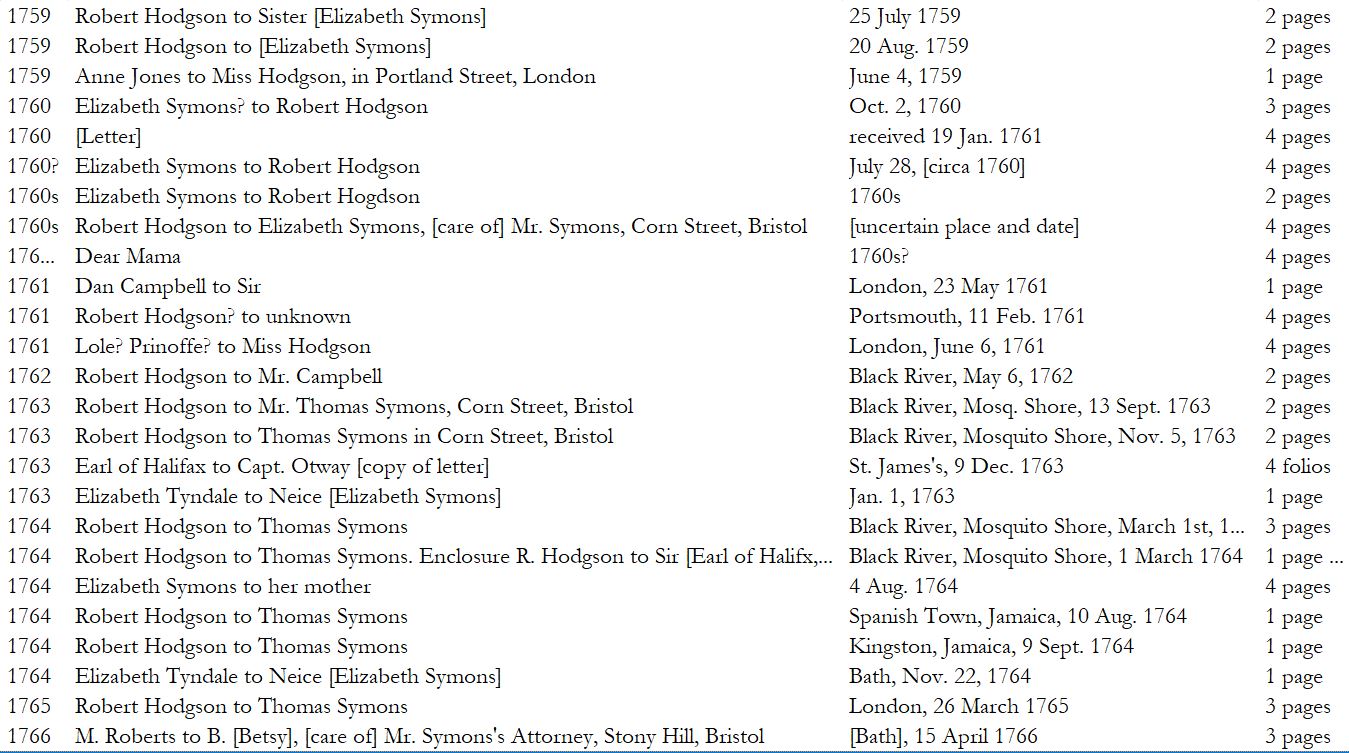

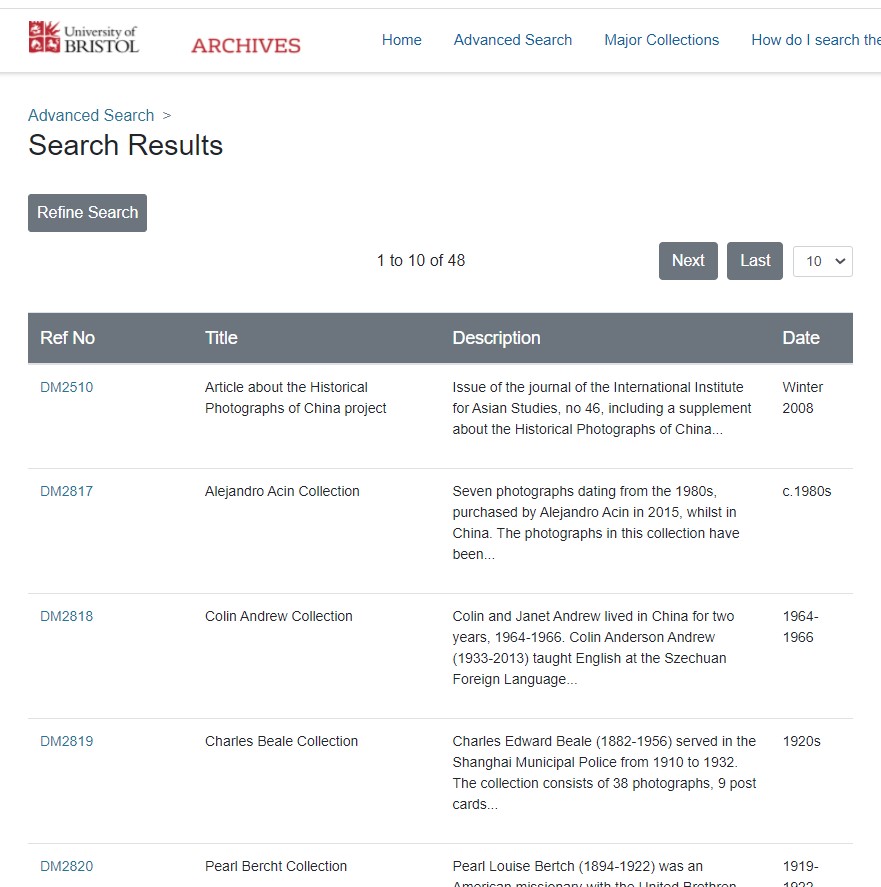

Fast forward seven years to October of 2021, and I was finally able to bequeath the entire trove of associated documents to the University of Bristol Library. The appropriately named, Peter Blencowe Collection (PBC), contains almost 300 letters and miscellaneous papers covering 1730 to the mid-nineteenth century. The collection has the reference number DM3028 and will be catalogued by library staff in 2023.

The collection offers much to scholars of the Georgian era of the greater Bristol area, the epistolary world of Atlantic families, and political events shaping the western Caribbean. Above all, the documents illustrate how multiple generations of Hodgsons maintained family, business, and social ties across the Atlantic.

Central America and the Caribbean. From Thomas Jefferys, A compleat chart of the West Indies, ‘The West-India atlas…’, London, 1775. Courtesy of United States Library of Congress.

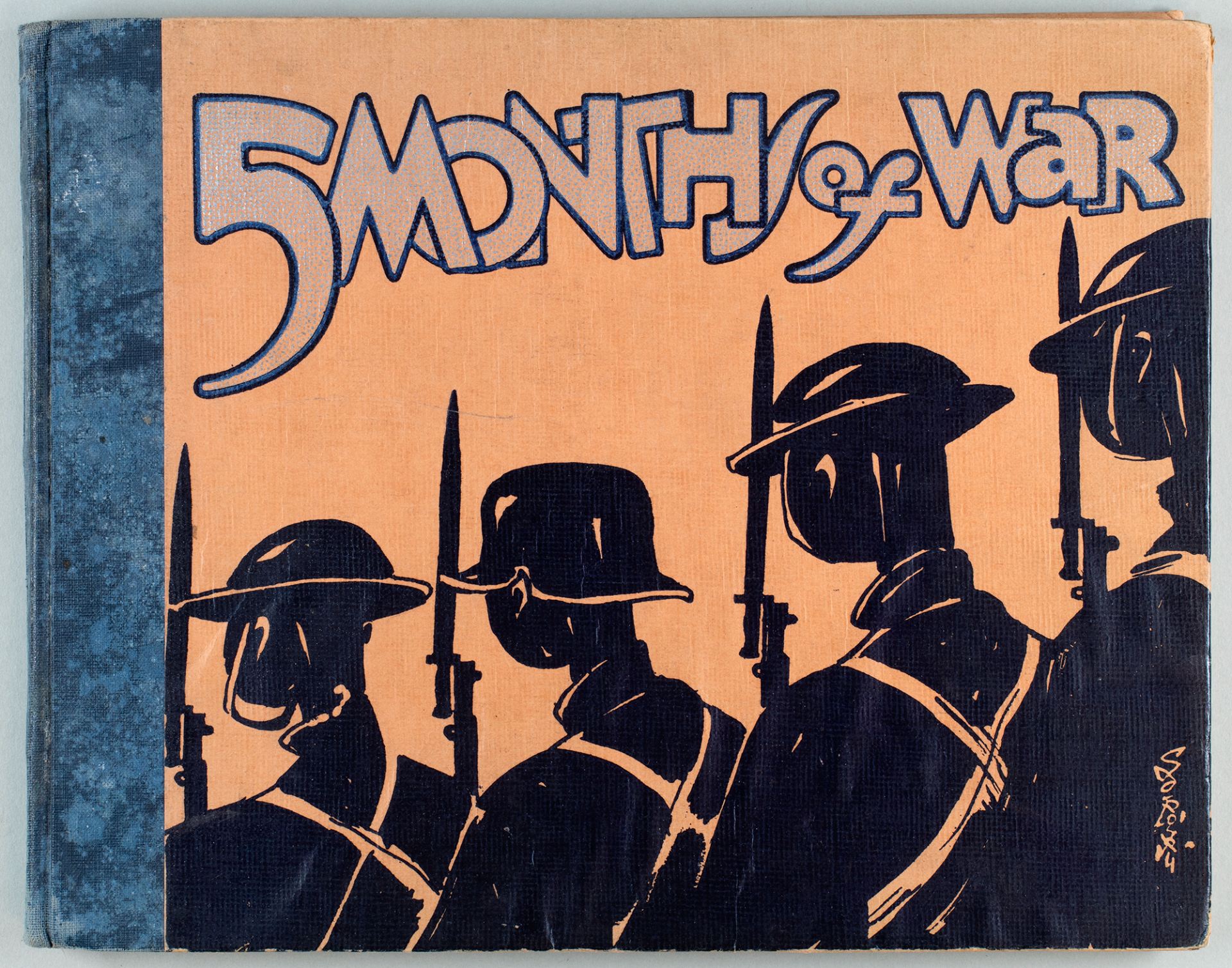

Readers interested in how we came to acquire this private collection are encouraged to peruse the full story in the second half of this post. The short version, however, must highlight the forethought and generosity of Mr. Peter Blencowe. Peter inherited the documents from the descendants of J.J. Blencowe whose first wife, Gratia-Maria Prowett Blencowe (1806-1840), was the grand daughter of Robert Hodgson II, the writer, receiver, or principal subject of the vast majority of the PBC. Peter worked diligently with the documents, and his published writings about the provenance and family significance of the collection can be found in The Hodgson Papers, Appendix VIII of the book The Blencowe Families: The Descendants of the Blencowe Families of Cumbria and Northamptonshire, edited by J.W. Blencowe and published in 2001 by The Blencowe Families Association in Oxford. Peter gave the collection to Caroline and I in 2016 under the condition that we would ensure its public availability.

Book cover of ‘The Blencowe Families’.

Central characters in the documents are members of the Hodgson family, including Robert Hodgson (father) and especially his son – also named Robert – both of whom served as British Superintendents for the Mosquito Shore (1749-1758; 1768-1775), a British outpost in eastern Central America that was always contested and claimed by Spain. The dominant force on the Shore, however, was the native Miskitu people whose leadership formed a political alliance known as the Miskitu Kingdom. The letters of Robert Hodgson I (the father) and Robert Hodgson II (the son), as well as letters from Robert II’s spouse, Mrs. Elizabeth Pitt Hodgson, and their four children, expose political intrigues in and beyond the contested borderland for much of the eighteenth century.

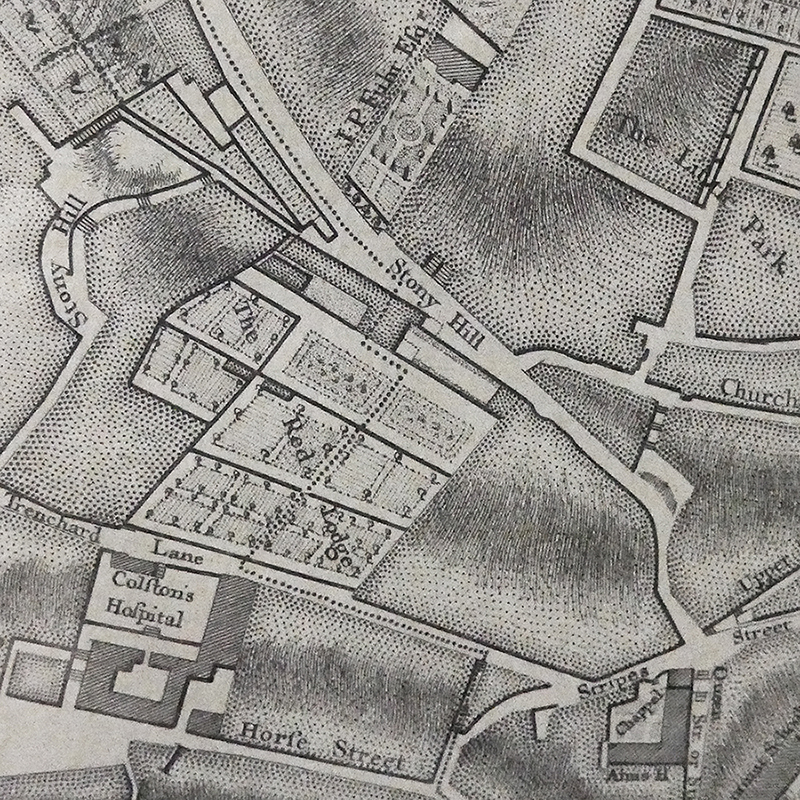

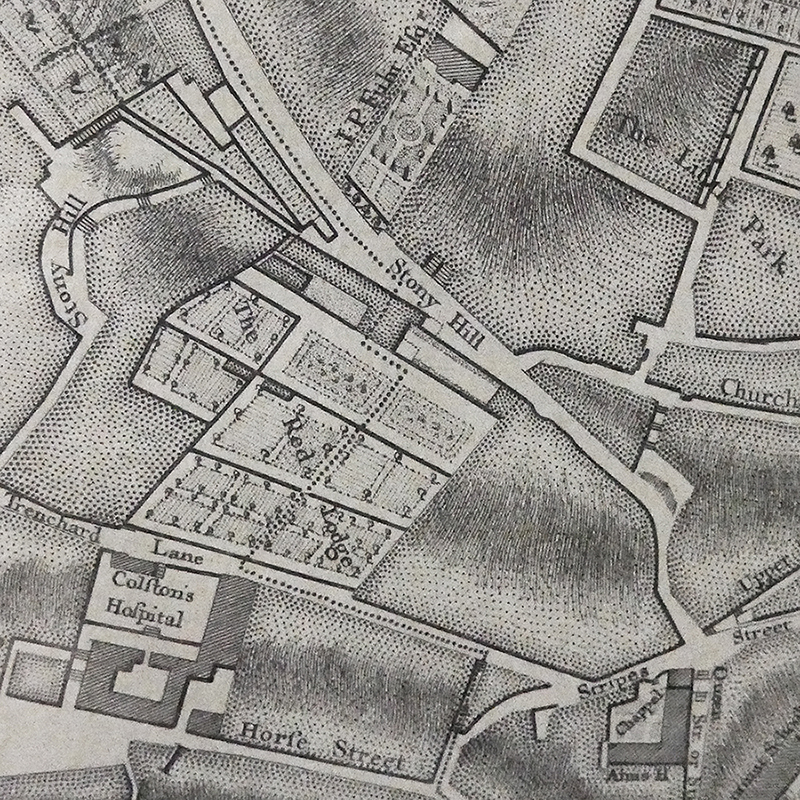

A particular highlight of the Peter Blencowe Collection is the letters that Elizabeth Hodgson Symons sent to her brother, Robert II, from her home in Stony Hill (part of which is now named Stoney Hill, part Park Row) in Bristol that she shared with her husband, the Bristol solicitor Thomas Symons, and their daughter Elizabeth (Betsy) Symons.

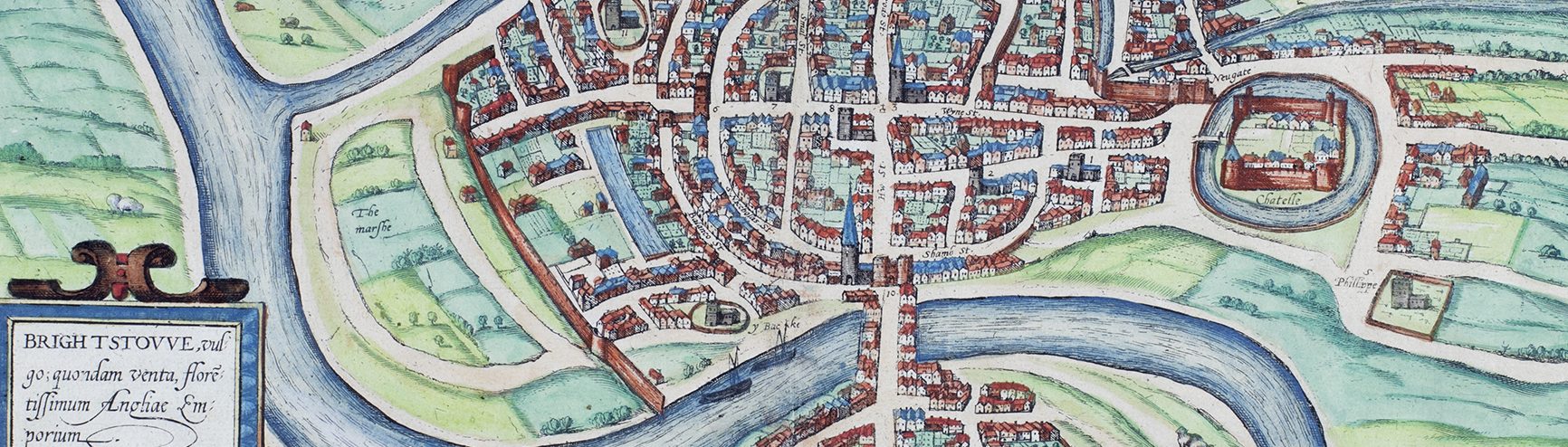

Part of ‘A Plan of the City of Bristol’, drawn and surveyed by John Rocque, engraved by John Pine, dated MDCCXLII, and published in March 1743. Courtesy of Special Collections, University of Bristol Library. Stony Hill (part of which is now named Stoney Hill, part Park Row) can be seen above and to the left of The Red Lodge

Between 1768 and 1776, Elizabeth Hodgson Symons sent 33 numbered letters to Robert II on the Mosquito Shore – sadly letters 9, 13, and 32 are missing. Her letters paused in 1776 because the British government recalled Robert II to answer charges of misconduct. When he returned to the Caribbean in 1780 as a colonel to advance the British assault along the Río San Juan in Nicaragua (along with compatriots Horatio Nelson and Edward Despard), his sister wrote him four more letters.

Elizabeth’s letters contain mundane gossip of Bristol, news from London, the prices fetched by Hodgson’s natural resources, and, especially, notices of relatives near and far, including the Tyndales of Bath and Bathford, Lords Delamere and Earls of Stamford, the Astronomer Royal, Nevil Maskelyne, whose sister Margaret Maskelyne married Robert Clive (Clive of India). In short, the epistolary world of Elizabeth Symons provides an intimate glimpse into eighteenth-century domestic life of an aspiring upper-middle class family and the role played by letters in passing along news, maintaining family relations, and strengthening commercial networks locally and across the Atlantic.

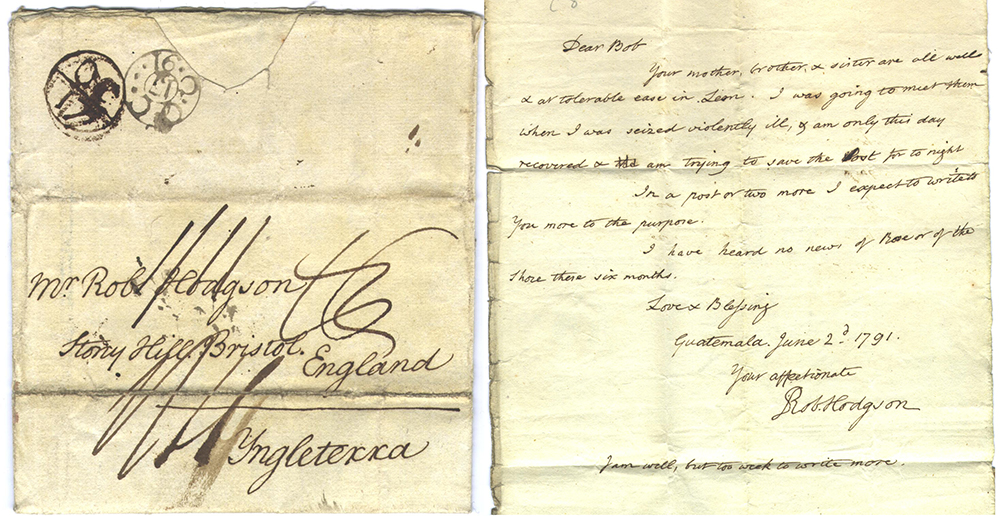

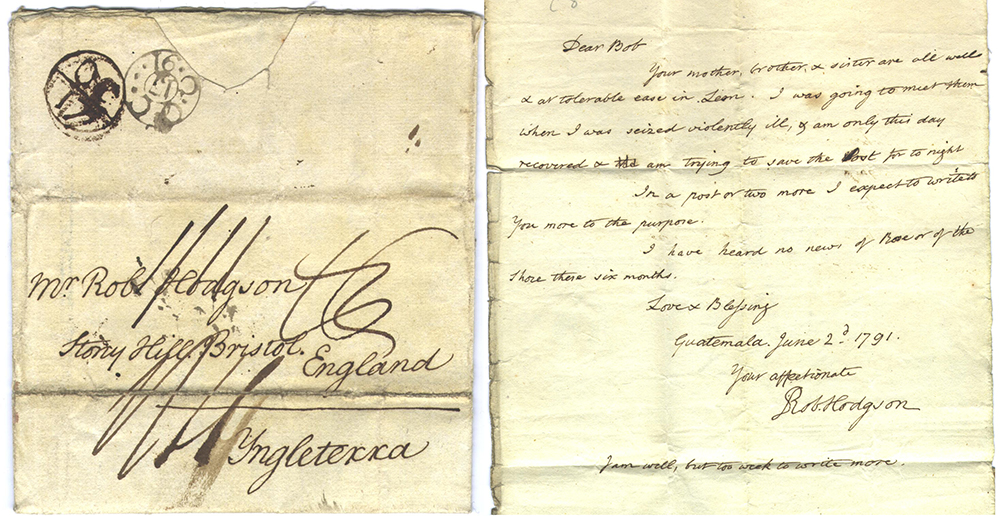

A second highlight of the PBC is a set of letters connecting Robert (Rob) Hodgson II (c.1737-1791) with his four children – William (Billy) Pitt Hodgson (1767-1800), Robert (Bob and Rob) Hodgson III (1769-1808), Martha Maria Hodgson (1774-1850), and Ariadne (Ari) Hodgson (1776-1792) – and his wife, Elizabeth (Betsy) Pitt Hodgson (1740-1797), over a period spanning the American War of Independence through his death in Guatemala City.

Letter from Robert Hodgson II in Guatemala to his son, Robert (Bob) Hodgson III, in Bristol, June 2, 1791, four days before he died. Courtesy of Yamil Kouri.

In a letter announcing their father’s passing, Robert Hodgson III assured his sister Martha Maria, ‘at the moment of his death (our father was a) Brigadier General, a Knight of the Order of Charles the third (the first foreigner who ever arrived to that most distinguished Spanish Title) with an appointment of 30,000 Dllrs. per ann. pension …’ Given that none of the family could attend his funeral, he sought to convince his sister that all due respects were paid: ‘The funeral cost three thousand Dollars which were paid by the King. He died a steady Protestant. The King of Spain has sent an express message of Condolence to my mother with his royal word that she and her Children are to be considered his peculiar protection’.

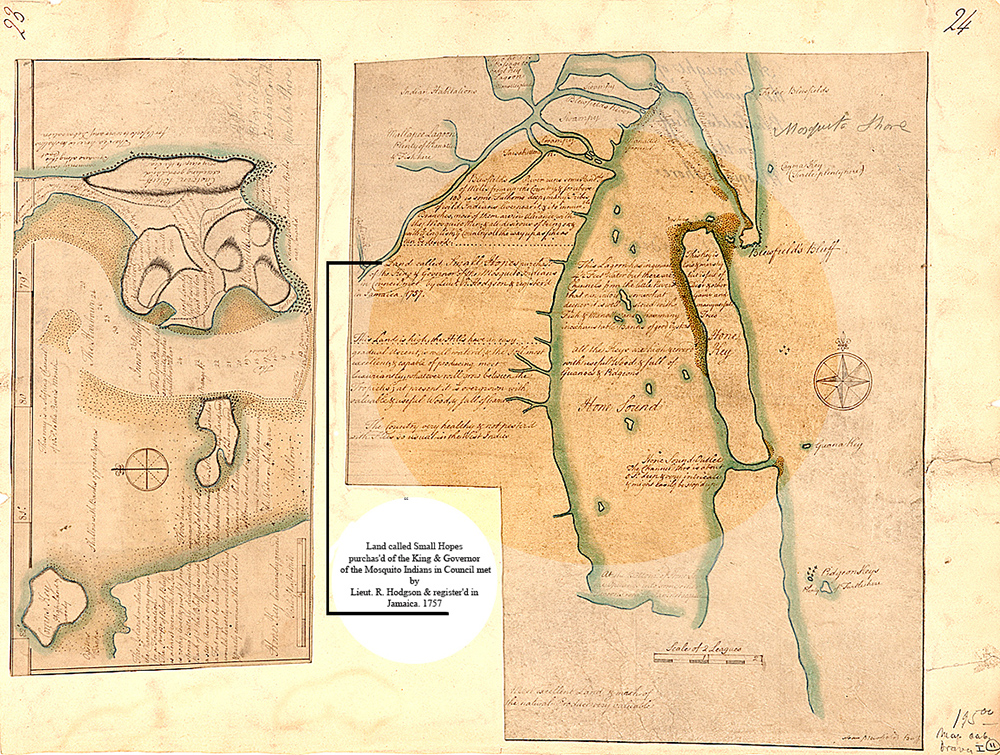

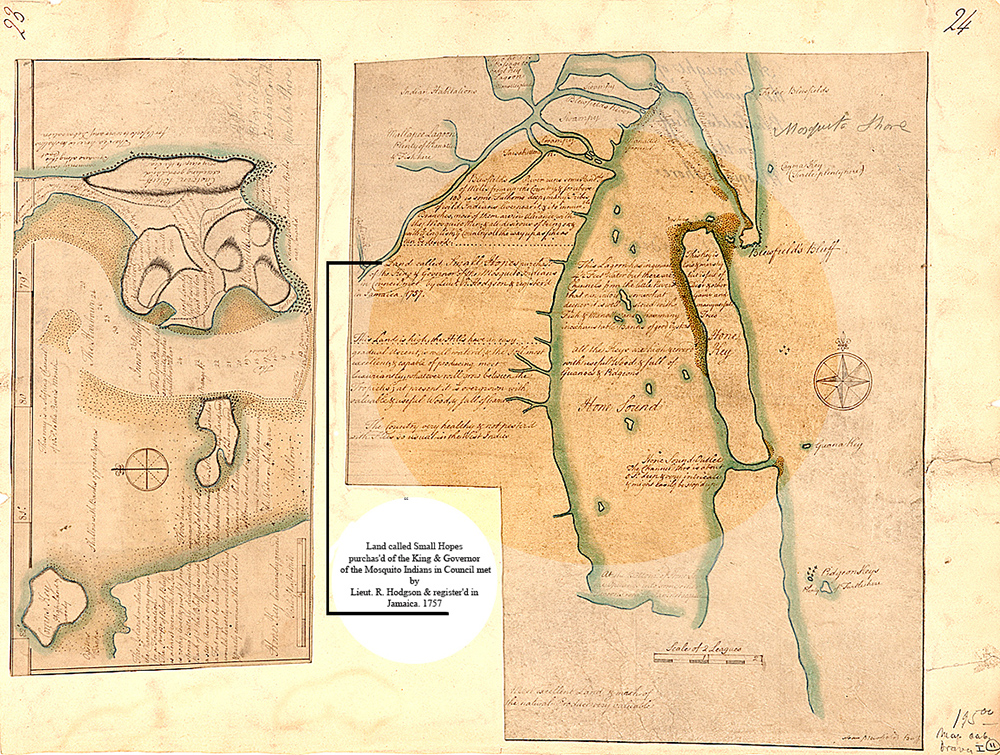

Maps of Bluefields drawn by Robert Hodgson II in 1770, in which he laid claim to the region by virtue of having purchased it from the Miskitu king and governor in 1757. Courtesy of the John Carter Brown Library, Brown University.

The revolutionary Atlantic was a time of significant upheaval for many families and the Hodgsons were no exception. Many family members were physically separated by great distances, and in order to stay in touch they needed to cooperate with Spanish authorities, especially following the British evacuation of the Mosquito Shore in 1787. When complex Shore tensions came to a head in 1790, a faction of Miskitu attacked and destroyed the Hodgson property at Bluefields. Robert II, Elizabeth, Billy, and Ari fled to Panama, and then to Nicaragua. Following Robert II’s death in 1791, the family fell on hard times and relied on the generosity of well-connected Spaniards in Central America. Surviving Hodgsons who reconnected at Corn Islands (Elizabeth, William, and Robert III) eventually had to seek refuge in Jamaica where they all died destitute. (Ari had died earlier as a fluent Spanish speaker in León, Nicaragua).

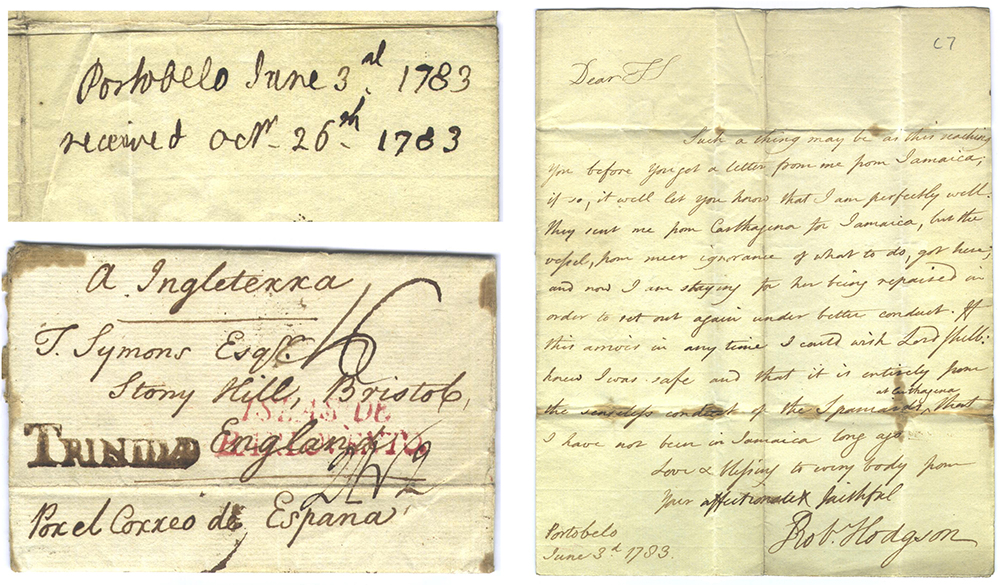

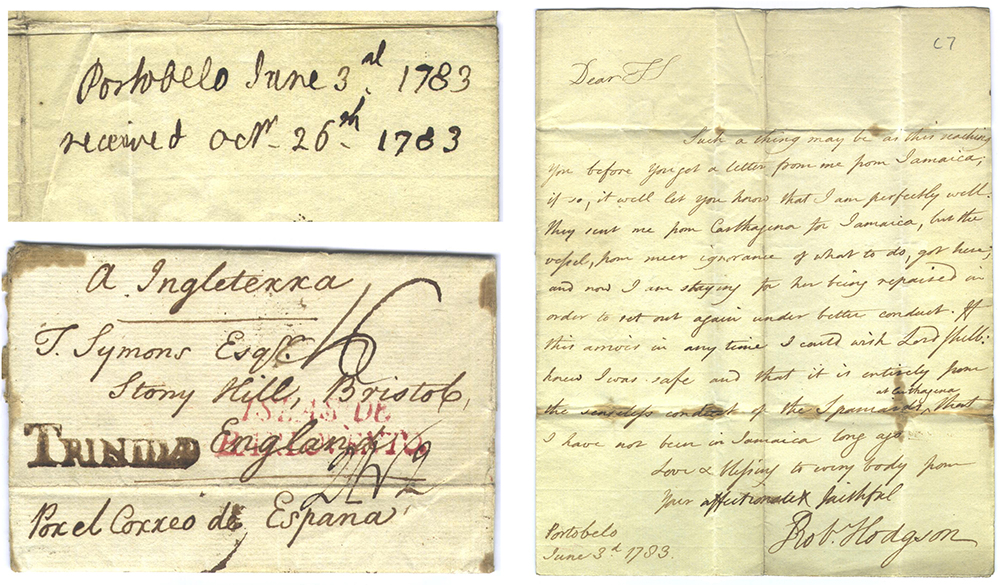

Robert Hodgson II’s letter to Thomas Symons from Portobelo, Panamá, informing his Bristol relations of his detention, June 3, 1783. Courtesy of Yamil Kouri.

At the very beginning of 1783, Robert Hodgson II was taken as a prisoner of war by a Spanish patrol ship off Portobelo, Panamá. For the next several years, he negotiated his position with the Archbishop of Santa Fé de Bogotá and Viceroy of Nueva Granada, Antonio Caballero y Góngora, while being detained in comfortable circumstances in Cartagena.

‘A Map of the Bay of Honduras and the Moskito Shore with the number of inhabitants and the commodities exported in 1782’, drawn by Colonel Robert Hodgson II and William Pitt Hodgson. At least 14 maps of different parts of the shore are attributed to Robert Hodgson II, but this is his magnum opus. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Virtual de Defensa de España.

Following the British evacuation of the Mosquito Shore specified in the Treaty of Versailles and the follow up Convention of London in 1786, Robert returned to Bluefields as a colonel in the Spanish Army. Hodgson’s ability to speak Miskitu and his knowledge of the region convinced Caballero y Góngora that he was needed to help bring the Miskitu leadership to Spanish interests. At least 50 letters in the PBC contain correspondence relating to the important decade of the 1780s. For scholars of the Mosquito Shore, the PBC complements the well-known collections covering the activities of Hodgson II held at the Archivo General de Simancas and other locations in Spain, Britain, and Colombia.

The Benjamin Franklin House, 36 Craven Street, London. Wikimedia Commons.

One of the great surprises of the PBC is its connections to the life of Dr. Benjamin Franklin. Franklin lived on Craven Street in London during two extended stays between 1757 and 1775. There, he lodged with the widow Mrs. Margaret Stevenson and became livelong friends with her daughter, Mary (Polly) Stevenson Hewson. Polly’s ‘dear friend’ from childhood was Mrs. Elizabeth (Betsy) Pitt Hodgson. Two months before she died in 1795, Polly had sent Martha Maria Hodgson a letter stating that she had known her mother Elizabeth for more than 40 years. Not surprisingly, Elizabeth Pitt is mentioned in several letters between Benjamin Franklin and Polly Stevenson, and Pitt and Franklin must have interacted on numerous occasions. The first of these letters, dated circa 1759, was written from Craven Street; Franklin signed off by presenting ‘my best respects to your good Aunts, and to Miss Pitt’. Scholars of Benjamin Franklin have not identified Miss Pitt as Mrs. Elizabeth Pitt Hodgson and now the PBC provides evidence for this and places it in a rich social context.

A stylized Spanish map by Luis Diez Navarro from 1765 showing the main British settlement at Black River in today’s Honduras. The map highlights the residence of William Pitt, the settlement’s 1732 founder, the grandson of a former governor of Bermuda, a distant relative of the eponymous British prime minister, and the father of Elizabeth Pitt Hodgson. Courtesy of the Biblioteca Digital Hispánica of the Biblioteca Nacional de España.

Elizabeth Pitt was born at Black River on the Mosquito Shore, the favourite daughter of the settlement’s founder, William Pitt, and a Spanish widow that William had rescued from the Miskitu following a shipwreck sometime in the late 1730s. Elizabeth (Betsy) Pitt married Robert Hodgson II in London in 1766, returning home by herself before her husband followed in 1768. Letters in the PBC reveal that Robert II spoke with Franklin during and after his courtship with Betsy in the mid-1760s.

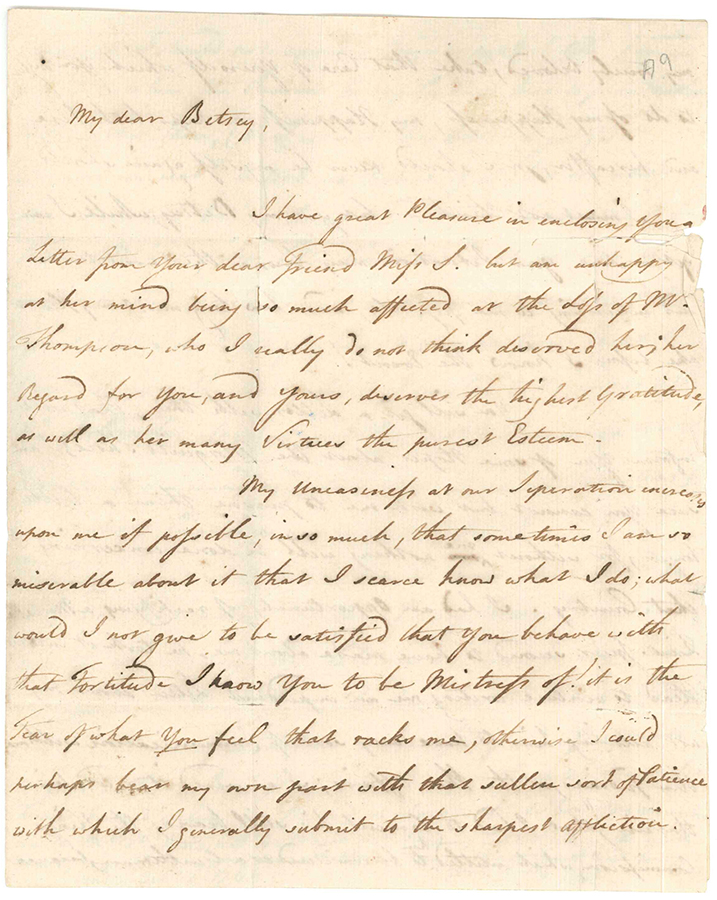

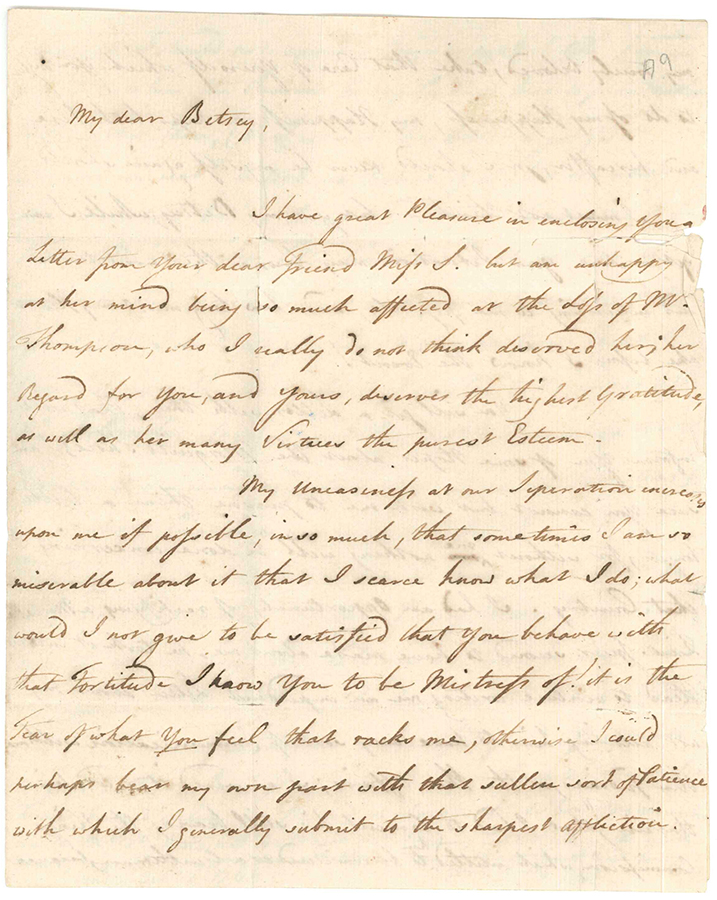

First page of a love letter from Robert Hodgson II writing from London to his wife, Elizabeth Hodgson, care of her father at Black River on the Mosquito Shore, Oct. 1, 1766. As he put it, ‘My uneasiness at our Separation increases upon me if possible, in so much, that some times I am so miserable about it that I scarce know what I do’. He did manage to enclose a letter to Betsy from her ‘dear friend’ Miss Stevenson.

At some point, Mary (Polly) Stevenson Hewson had loaned Robert II money. Her will of 1794 – available in The National Archive at Kew, and which varies in significant ways from the published version – testifies to her friendship with Elizabeth: ‘I bequeath to my friend Elizabeth Hodgson the Bond with all the Money due to me from her deceased Husband Robert Hodgson. It is a small mark of the Love I bear her’.

Much more can be said about the traces of Benjamin Franklin in the PBC, and to his poorly known connections to the Mosquito Shore more broadly – including the fact that his only daughter with his common law wife, Deborah Read, Sarah Franklin, married Richard Bache, the brother of Deborah Otway (née Bache), the wife of Mosquito Shore Superintendent Captain Joseph Otway whose appointment was situated between those of Robert Hodgson I and Robert Hodgson II. But that will have to await another venue.

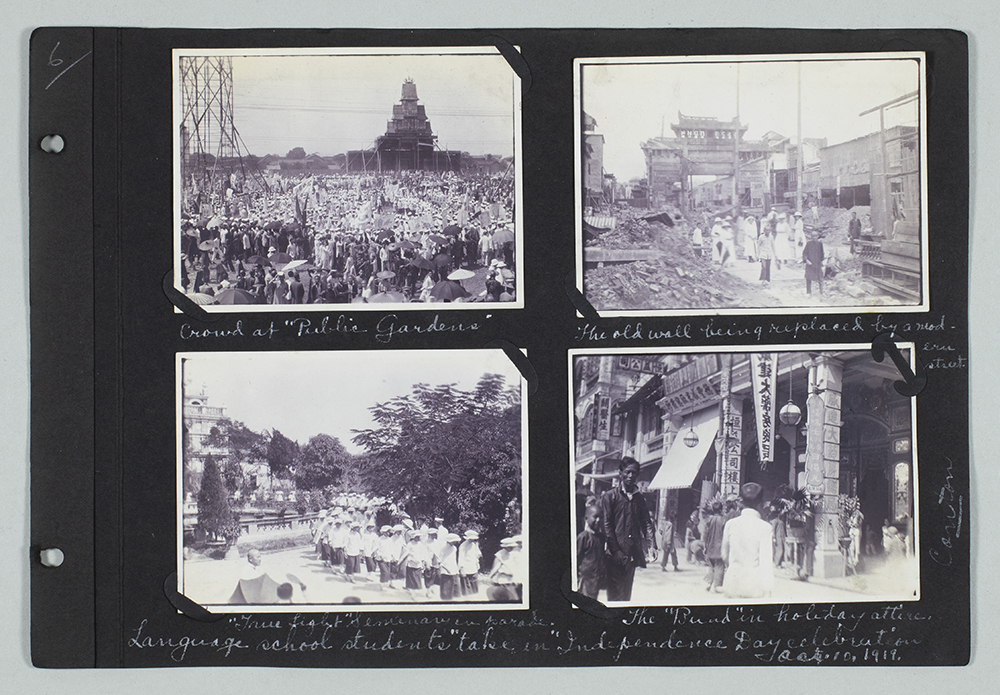

Four watercolours by an unknown traveller dated to July 1845 showing dwellings in Bluefields on the Mosquito Shore at the beginning of a new British protectorate. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Family members presumably preserved these documents in hopes of recovering property in Central America. Hodgson II’s oldest daughter, Martha Maria Hodgson Prowett, and especially her husband, the Rev. John Prowett (d. 1851), fought long and hard to acquire Hodgson’s property at Bluefields, or to receive monetary compensation from the Spanish government, and later from the Federal Republic of Central America, and finally from British officials seeking to establish a protectorate at Bluefields (see Colonial Office 123/61; 123/78 at The National Archive). A dozen letters in the PBC document Prowett’s correspondence with British ministers, lawyers, embassy staff, and even a hired investigator who retained a translator in Guatemala to dig into Hodgson II’s possessions at the time of his death. The documents suggest that Prowett became obsessed with his quest, and that his repeated failures ultimately consumed him.

Two letter covers from Robert Hodgson III to his sister, Martha Maria Hodgson, in Bristol. Left: from Blewfields, 17 April 1792, reporting on his return to the Shore. Courtesy of Jesús Sitja Prats. Right: reporting from Corn Island, 1 August 1792, after the family was once again forced to flee Bluefields. Courtesy of Yamil Kouri.

Although the Rev. Prowett emphatically claimed his wife was the last living heir and thus the rightful owner of Robert Hodgson II’s property, including his rumoured pension of 30,000 dollars held in Cartagena, this was not completely accurate. In his Jamaican will of 1807, Robert Hodgson III, left a portion of any share of his father’s pension to the children he shared with his domestic partner Mary Pitt, Catharine Maria Hodgson and Robert Pitt Hodgson. Mary and her children were of African descent and could have also laid claim to Robert Hodgson II’s property and pension. Indeed, the many Hodgsons of today’s Nicaragua and to a lesser extent Jamaica almost certainly trace their ancestry in some way to Catharine or Robert Pitt Hodgson, Robert Hodgson II, Robert Hodgson III, or William Pitt Hodgson.

By the early nineteenth century, many Creole Hodgson descendants resided at Bluefields and likely elsewhere such as Corn Island. More than 20 percent of 53 property lots registered on an 1846 map of Bluefields were owned by Hodgsons with different first names, suggesting they had claimed Robert II’s property on their own (see Foreign Office 53/5 at The National Archive).

How did we learn about these documents?

Caroline and I had been exchanging emails for many years when we finally met in person at The Tap on the Line, a Kew Gardens pub, in the summer of 2014. There we hatched a plan to write a book about Robert Hodgson II. Each of us had been working separately with Hodgson’s diplomatic writings found in Britain, Spain, Colombia, and in other depositories around the Atlantic (e.g. the William Clements Library at the University of Michigan), for over a decade.

My chance reading of ‘The Hodgson Correspondence: 18th Century Mail from the Western Caribbean to England’ – a 2003 article by Yamil H. Kouri, Jr., and Leo J. Harris, published by the Postal History Journal – altered the scope of our research. The article discussed some unusual Hodgson family letters sent from Bluefields, Corn Island, and León, Nicaragua, to Bristol via Spanish carriers. Through daily correspondence with Yamil and, then with his fellow philatelists Leo Harris, Brian Moorhouse, Neal West, Bill Byerley, Mike Birks, and Jim Mazepa, I was initiated into an unknown (to me) world of enthusiastic collectors and knowledgeable Nicaraguan historians. From the good will of these individuals, and especially Yamil Kouri, I received numerous scans of Hodgson family letters that collectors had purchased for their rare postal markings. They were more than willing to provide me with scans, and some of their letters are shown in this post – because these particular letters remain in private collections, the PBC only holds photocopies of them.

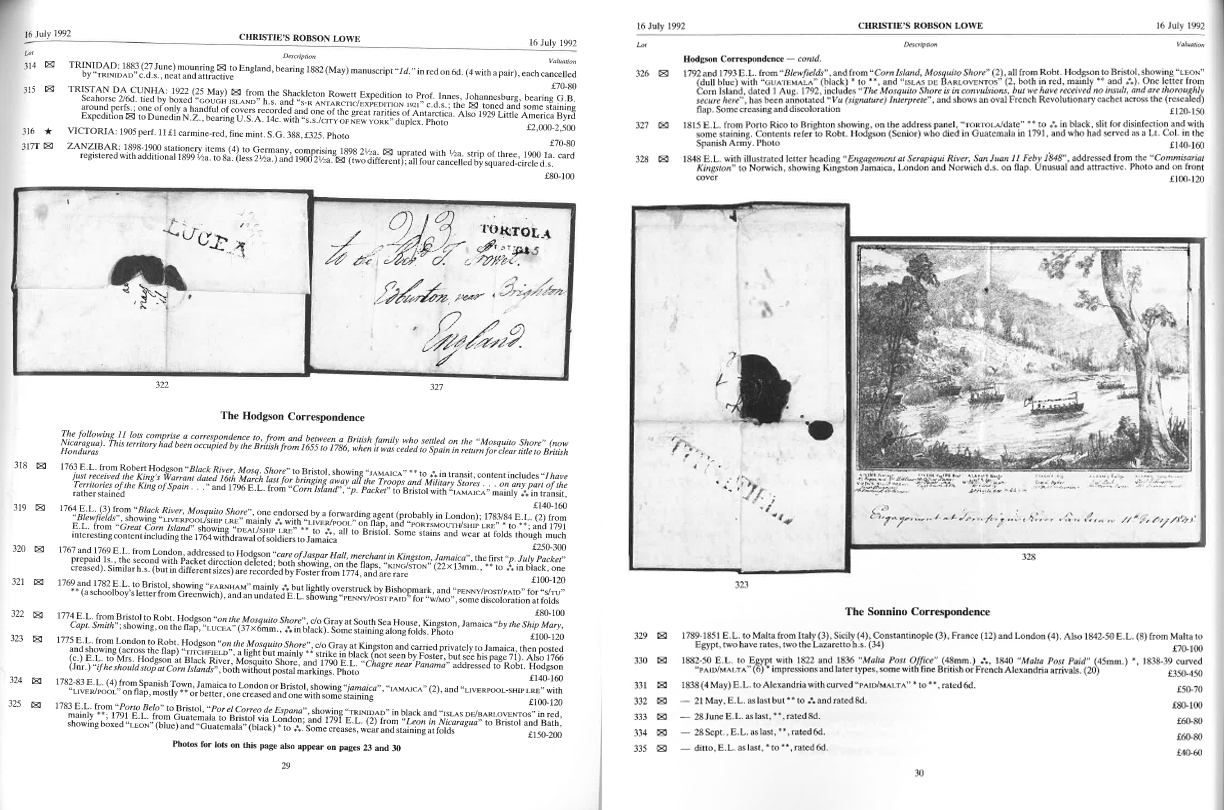

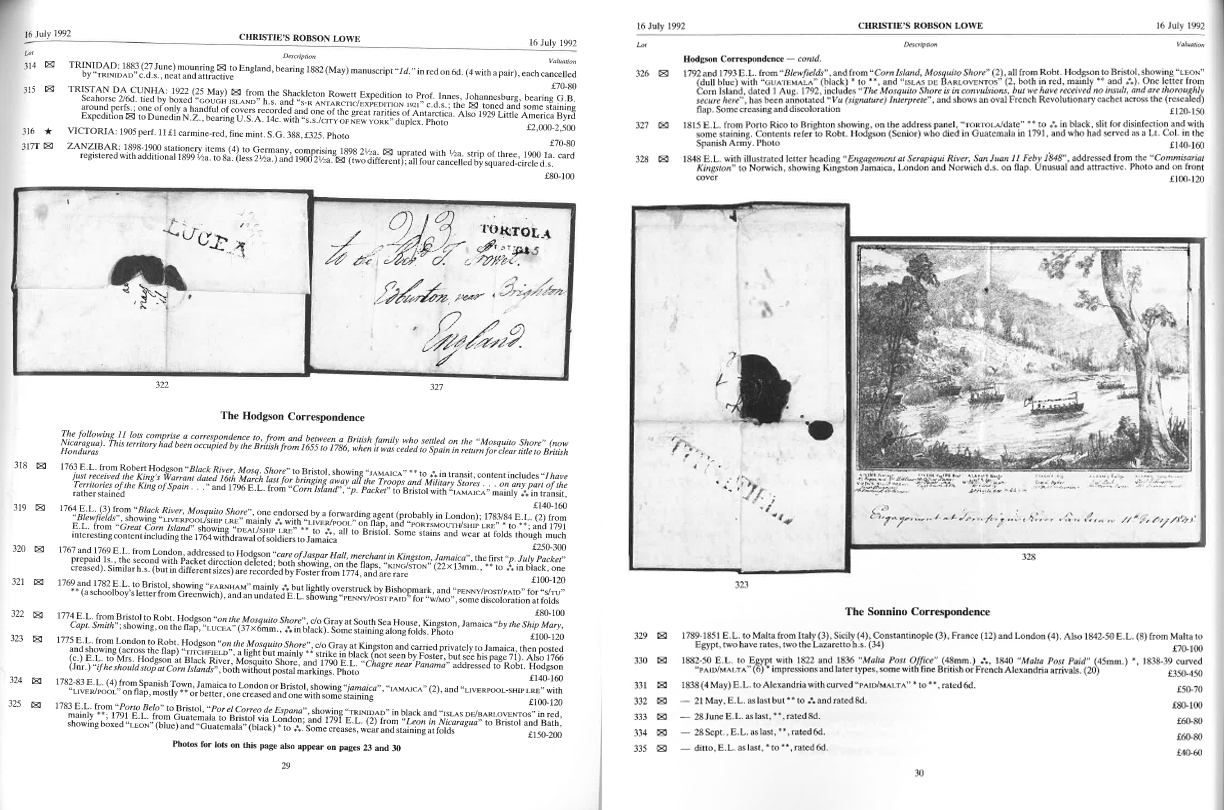

When I told Caroline of this correspondence she replied, ‘I can’t begin to tell you how excited I am about this discovery’. We learned that 21 letters had been sold during a Christie’s Robson Lowe auction on 16 July 1992. This got Caroline and I thinking about who had sold these letters and, more importantly, if there might be more of them.

Two pages from Christie’s Robson Lowe Catalogue, London, 16 July 1992, showing the sale of the lots 318 to 328 referred to as ‘The Hodgson Correspondence’. Courtesy of New York Public Library.

After finding a review of The Blencowe Families book mentioned earlier, Caroline reached out to Peter Blencowe in an email explaining our interest in the Hodgsons. Peter quickly wrote back, confessing that he had ‘been waiting for an email or letter like (hers)’ for a long time. When Caroline planned a trip to meet with Peter in person in the summer of 2016, he told her ‘to bring an empty suitcase’.

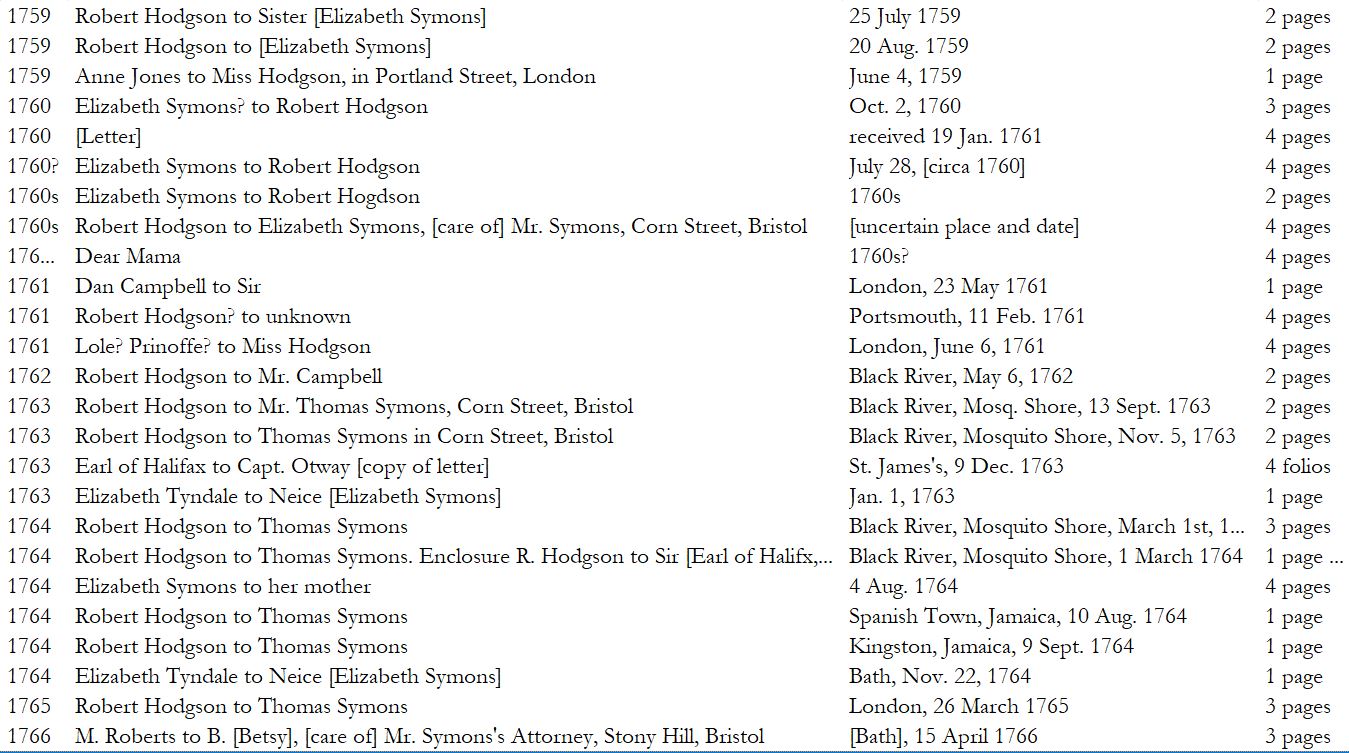

Screen capture of a database showing a small portion of our early efforts to catalogue the Peter Blencowe Collection.

In the summer of 2017, Caroline and I sat down together in her home in Bristol and did a quick reading of all the documents and a cursory cataloguing of the entire collection. Although we always planned to give the papers to the University of Bristol Library, Caroline’s sudden hospitalization, unexpected passing, and the Covid-19 pandemic delayed the transfer until the autumn of 2021. Thanks to the special care of the documents by Caroline’s husband, Richard Williams, and Gina Robinson, who helped Richard organize Caroline’s papers, the documents are now safe with Special Collections.

In her last email to me, and not hinting at any worrisome health conditions, Caroline offered her commentary on a paper I was presenting on Robert Hodgson II at the Annual Conference of the Omohundro Institute in 2019.

She wrote to say, ‘my inclination would be to emphasise again in the conclusion of the paper the significance of the PBC! What it allows us to do, among many other things, is to delve into and juxtapose the professional and personal aspects of Hodgson’s life, his wider family, the role that close relations (Elizabeth & Thomas Symons, John Peighin, etc played in facilitating his trading activities, the way family fortunes may have motivated his or his father’s adventuring and the impact of these on his children), how their letters shed light on the ways in which a close family maintained contact and – for the Hodgsons – a sense of belonging and identity.’ And so I did, and so I shall.

Special Collections at the University of Bristol holds the largest and longest established collection of election addresses (over 30,000) and campaign literature, from all British parliamentary elections since 1892. We also hold leaflets from London County Council and European parliamentary elections, along with campaign literature from other important national plebiscites such as the 1975 and 2016 referendums on membership of the European Union. This material is available for consultation by students, researchers, journalists, and members of the public.

Special Collections at the University of Bristol holds the largest and longest established collection of election addresses (over 30,000) and campaign literature, from all British parliamentary elections since 1892. We also hold leaflets from London County Council and European parliamentary elections, along with campaign literature from other important national plebiscites such as the 1975 and 2016 referendums on membership of the European Union. This material is available for consultation by students, researchers, journalists, and members of the public. A description of our political collections, including our election address archive, can be found at:

A description of our political collections, including our election address archive, can be found at:

This kaleidoscope mechanical chromotrope magic lantern slide for children dates from around 1870-1880. The slide has two panels and was designed to be inserted into a lantern slide viewer. The handle of the viewer would be turned, so that one panel would move while the other remained stationary, giving a kaleidoscope effect. The slide comes from a collection donated to us by Paul Raphael in February 2023.

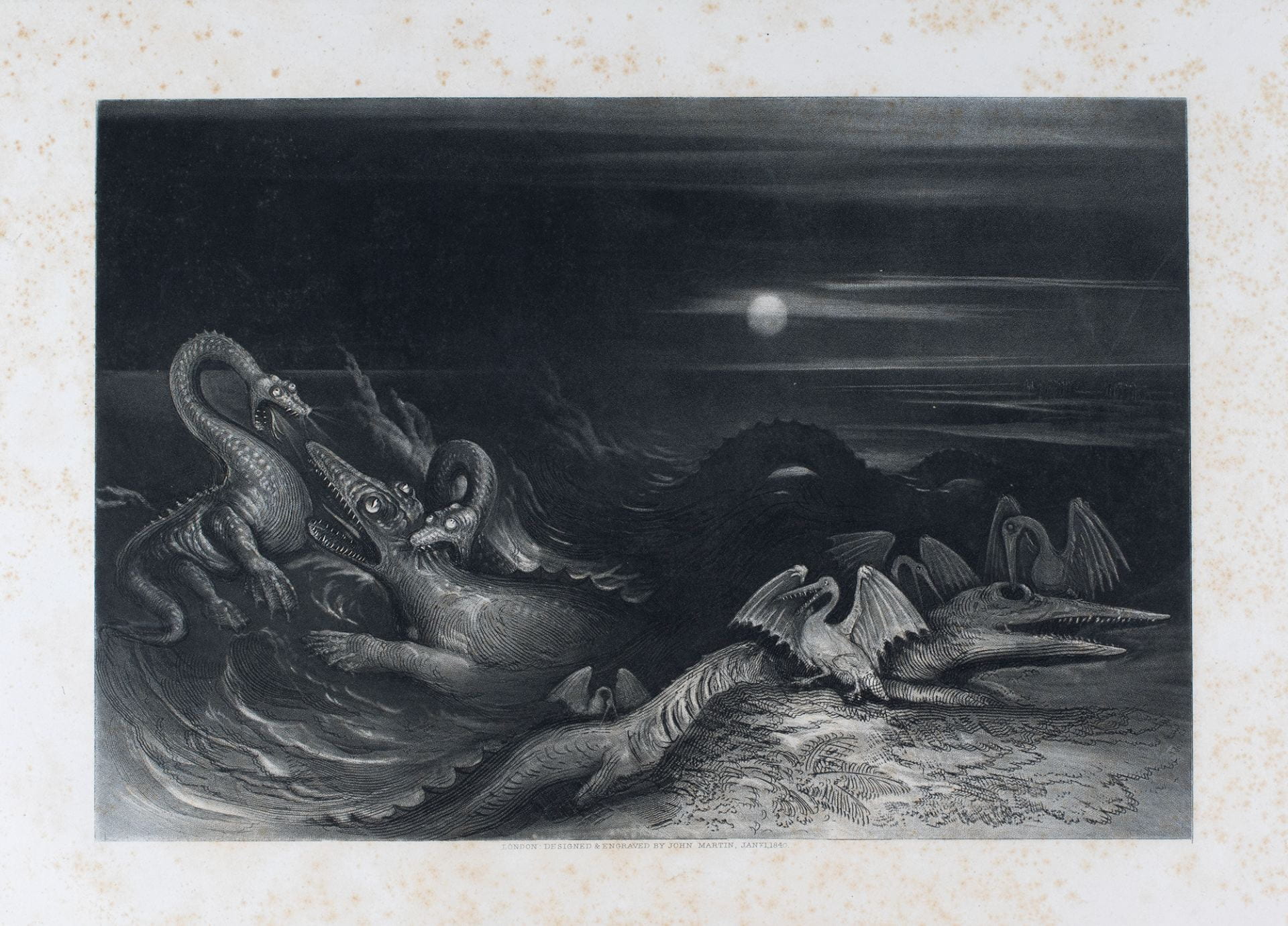

This kaleidoscope mechanical chromotrope magic lantern slide for children dates from around 1870-1880. The slide has two panels and was designed to be inserted into a lantern slide viewer. The handle of the viewer would be turned, so that one panel would move while the other remained stationary, giving a kaleidoscope effect. The slide comes from a collection donated to us by Paul Raphael in February 2023. John Martin (1789-1854) was an English Romantic artist, known for his dramatic, apocalyptic scenes. The engraving, The Sea-Dragons as they lived, depicts plesiosaurs attacking an ichthyosaur, while pterosaurs feed on the body of a second ichthyosaur. It forms the frontispiece to The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons by Thomas Hawkins, published in 1840. Thomas Hawkins (1810-1889) was a Somerset fossil collector, who collected fossils from Lyme Regis and the Dorset coast, which are now held in the Natural History Museum.

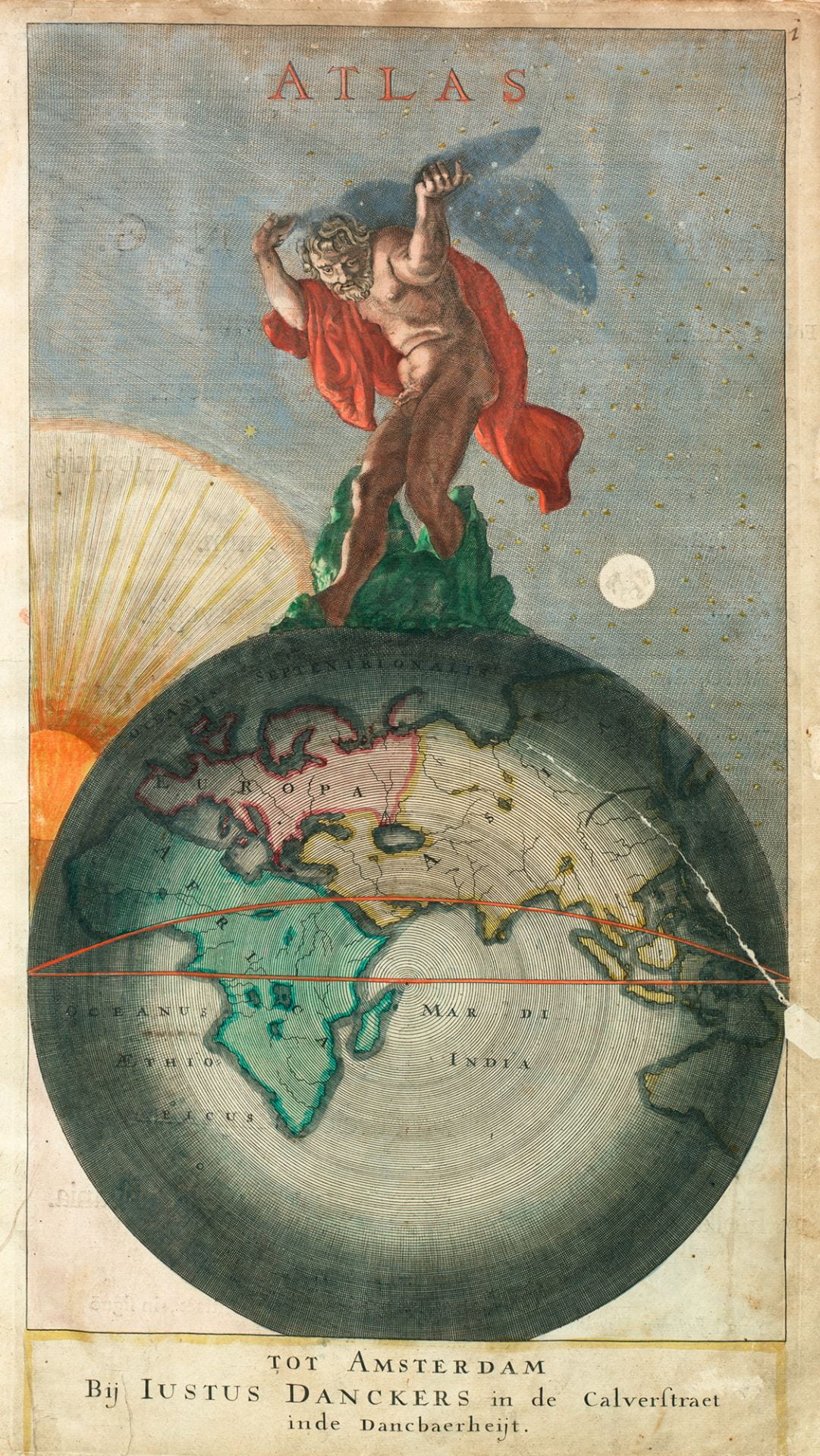

John Martin (1789-1854) was an English Romantic artist, known for his dramatic, apocalyptic scenes. The engraving, The Sea-Dragons as they lived, depicts plesiosaurs attacking an ichthyosaur, while pterosaurs feed on the body of a second ichthyosaur. It forms the frontispiece to The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons by Thomas Hawkins, published in 1840. Thomas Hawkins (1810-1889) was a Somerset fossil collector, who collected fossils from Lyme Regis and the Dorset coast, which are now held in the Natural History Museum. The title page from an atlas of 1690, produced by Justus Danckerts (1635-1701) who was part of a Dutch family of mapmakers, based in Amsterdam. The illustration depicts the titan, Atlas, holding up the sky. Our copy of the atlas came to the University of Bristol Special Collections as part of the Bristol Moravian Church Archive.

The title page from an atlas of 1690, produced by Justus Danckerts (1635-1701) who was part of a Dutch family of mapmakers, based in Amsterdam. The illustration depicts the titan, Atlas, holding up the sky. Our copy of the atlas came to the University of Bristol Special Collections as part of the Bristol Moravian Church Archive.

![A Cartier-Bressonesque photograph by Cyril Whitaker, captioned in the album: ‘Calibrating a [petroleum] tank by pumping out and weighing water on alternate scales. Jan. 1938’ (HPC ref: CW08-80). Whitaker was a talented ‘semi-pro’ photographer who documented the Asiatic Petroleum Company (APC) installation near Chongqing. Cyril Whitaker Collection, DM2845/8.](https://specialcollections.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2022/01/12.-CW08-80.jpg)