A guest blog by Helen Clutton, a MA Medieval Studies student, recalling a placement with Special Collections earlier this year

If you ask most Bristol students to describe Special Collections they will probably say, ‘It’s a couple of rooms on the first floor of the Arts & Social Sciences Library, and if you ask them very nicely they’ll magically produce a book out of nowhere, which you can come in and look at as long as you put it on a cushion.’

Special Collections Seminar Room laid out in preparation for a seminar on the history of Hong Kong. Photograph by Jenny Fisken.

That’s how I thought of Special Collections, before I did a placement there as part of my masters. Every Tuesday for a semester I spent some time with a member of Special Collections staff (there are more than you think!) and learnt a little bit about everything that goes on in this branch of the library service. What we see on that first floor is the tip of a remarkable iceberg.

Downstairs, along corridors, and through various locked doors, there is a treasure trove of archived material, acquired over a century, covering not just books but artworks, banners, political leaflets, photographs – you name it, it’s down there (and if it’s not in the library building, it’s in the off-site warehouse in Brislington). And the collection grows every year – last year alone there were sixty new acquisitions. There are also specific projects going on, such as one for the Hong Kong History Centre, where wonderful photos and memories of old Hong Kong are being sent in by people from all over the world. Additionally, Special Collections is linked with Theatre Collections just down the road – another amazing accumulation of riches. So much history, so many stories, all there to be discovered.

King George V and Queen Mary passing the Vandyck Printworks (now the Theatre Collection) on their way to open the King Edward VII Memorial Hospital (BRI) on Park Row, 28 June 1912.

For instance, the stories which have been holding my attention for all these weeks centre around DM104, which is a collection of fifty manuscripts from Kingswood Abbey in Gloucestershire (now no longer in existence apart from its gatehouse, thanks to our old friend Henry VIII). These documents cover two centuries of monastic life, and include land deals, estate accounts, lists of workers’ jobs, and complaints about taxes! There are frustrating gaps and so many unanswerable questions (thanks again, Henry); however, the documents we do have reveal a dynamic and far-reaching monastic enterprise, with lands up to thirty miles away. Some of their lands were received as gifts, perhaps to secure the prayers of the monks (‘for the salvation of my soul’); other lands were part of complicated exchanges or leases where, in the days before birds-eye-view maps, plots were described in relation to people or landmarks around them. We can see in these descriptions a local and generational knowledge which, even when lessened by the Black Death, is still present at levels unimaginable now.

List of properties owned by Kingswood Abbey and the wages paid to workers at each property, 1255-1256. SC ref: DM104/24.

The documents relating to estate management give a tantalising snapshot of abbey life – the trips they took, the animals and their keepers, the food they ate (so much fish!). Being immersed in these documents over weeks transforms dry old documents into living stories.

And that’s the most interesting part of Special Collections – how do we discover all these stories? How do we know what we’ve got? That’s the job of the archivists. They take an acquisition, which could be an immaculate collection or simply a pile of ‘stuff’ from someone’s attic; they quarantine it in case of pests and mould; they do a simple box list of the contents; then when time, money, and manpower allow, they decide how best to arrange it, list it, and describe it, they digitise it if appropriate, and they make it accessible to us.

It’s quite an undertaking, and the people doing it are highly skilled and dedicated. They are also overstretched and underappreciated! Every time one of us students makes a request for an item from Special Collections, there’s a whole lot of form filling, shelf searching, and running up and down stairs that goes on in order to get that item onto its cushion – so remember to thank them.

![Illustrated page from the ‘Ave Beppo scrapbook’ [c1903] created by Margaret Vaughan [née Symonds], the daughter of John Addington Symonds (DM3271/9/1/3/1).](https://specialcollections.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2025/06/DM3271-9-1-3-1-001.jpg)

![Portrait photograph of John Addington Symonds from an album of photographs, sketches and cuttings [c1894] created by Margaret Symonds (DM3271/10/1/4/1).](https://specialcollections.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2025/06/DM3271-10-1-4-1-001.jpg)

![The pros and cons of living in Davos and Egypt [c1876] (DM3271/7/2/2 ).](https://specialcollections.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2025/06/DM3271-7-2-2-001.jpg)

Special Collections at the University of Bristol holds the largest and longest established collection of election addresses (over 30,000) and campaign literature, from all British parliamentary elections since 1892. We also hold leaflets from London County Council and European parliamentary elections, along with campaign literature from other important national plebiscites such as the 1975 and 2016 referendums on membership of the European Union. This material is available for consultation by students, researchers, journalists, and members of the public.

Special Collections at the University of Bristol holds the largest and longest established collection of election addresses (over 30,000) and campaign literature, from all British parliamentary elections since 1892. We also hold leaflets from London County Council and European parliamentary elections, along with campaign literature from other important national plebiscites such as the 1975 and 2016 referendums on membership of the European Union. This material is available for consultation by students, researchers, journalists, and members of the public. A description of our political collections, including our election address archive, can be found at:

A description of our political collections, including our election address archive, can be found at:

This kaleidoscope mechanical chromotrope magic lantern slide for children dates from around 1870-1880. The slide has two panels and was designed to be inserted into a lantern slide viewer. The handle of the viewer would be turned, so that one panel would move while the other remained stationary, giving a kaleidoscope effect. The slide comes from a collection donated to us by Paul Raphael in February 2023.

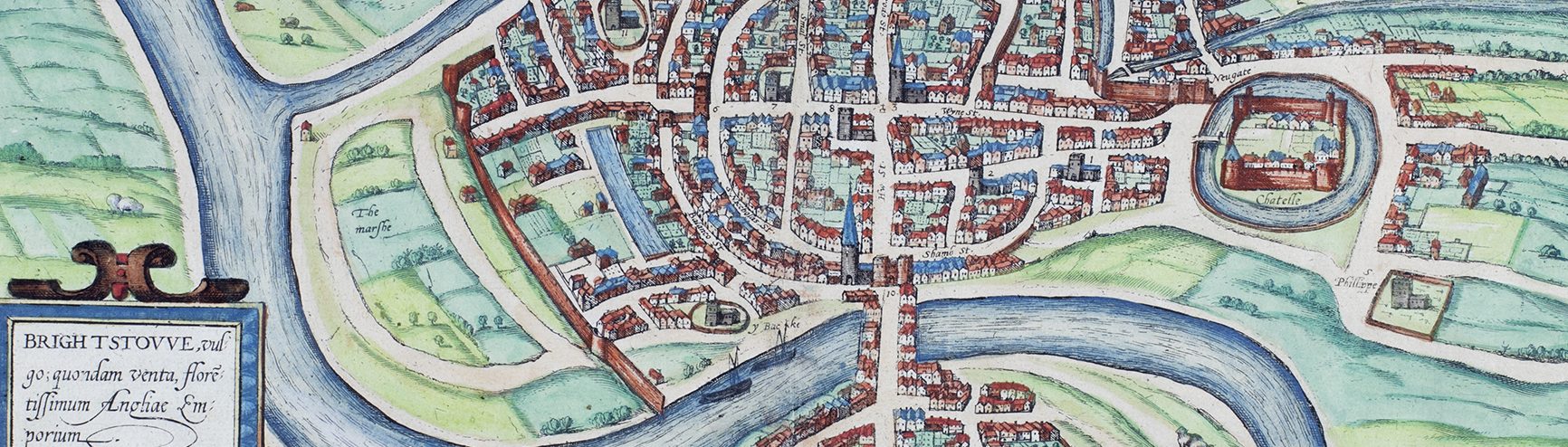

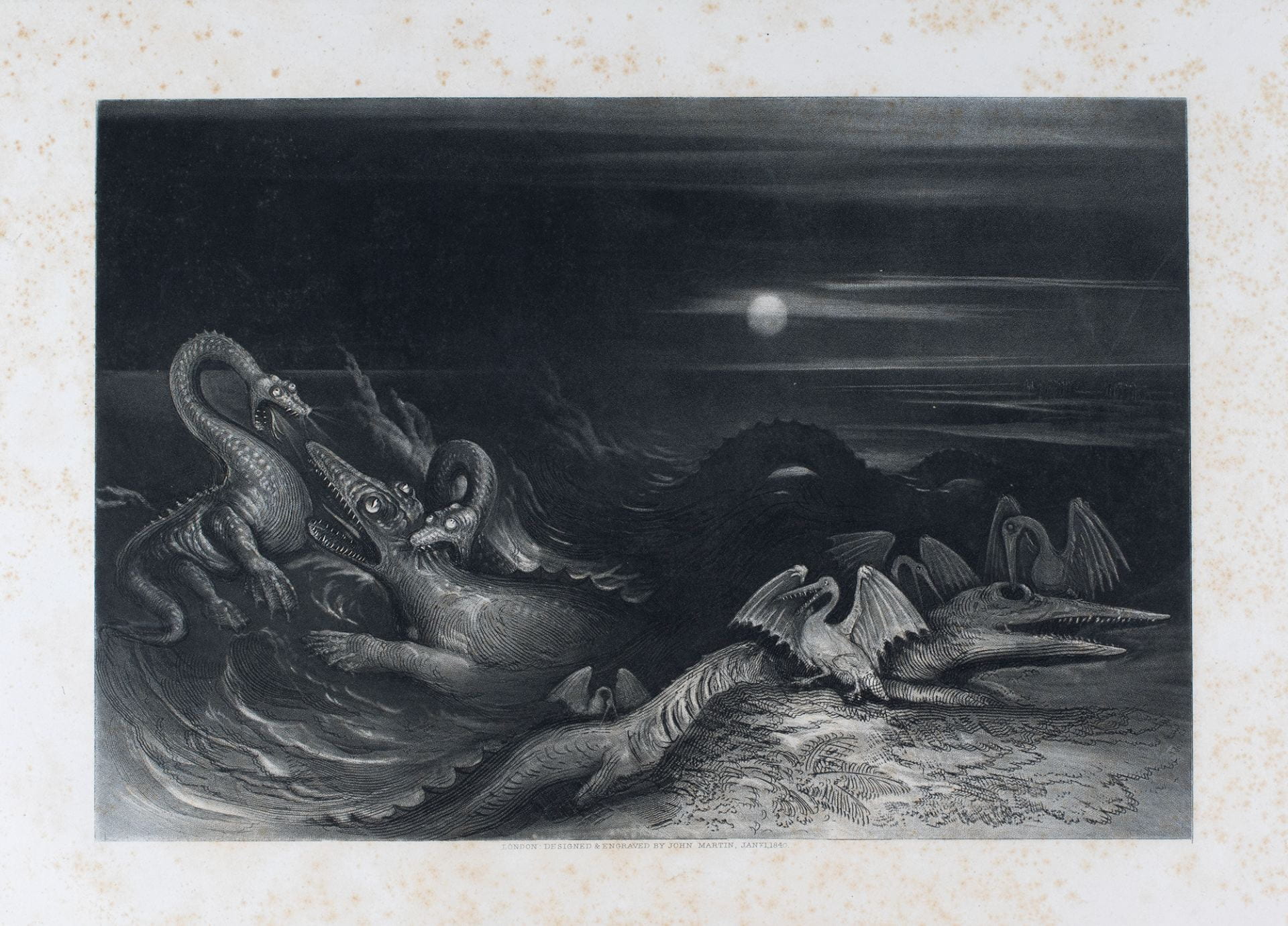

This kaleidoscope mechanical chromotrope magic lantern slide for children dates from around 1870-1880. The slide has two panels and was designed to be inserted into a lantern slide viewer. The handle of the viewer would be turned, so that one panel would move while the other remained stationary, giving a kaleidoscope effect. The slide comes from a collection donated to us by Paul Raphael in February 2023. John Martin (1789-1854) was an English Romantic artist, known for his dramatic, apocalyptic scenes. The engraving, The Sea-Dragons as they lived, depicts plesiosaurs attacking an ichthyosaur, while pterosaurs feed on the body of a second ichthyosaur. It forms the frontispiece to The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons by Thomas Hawkins, published in 1840. Thomas Hawkins (1810-1889) was a Somerset fossil collector, who collected fossils from Lyme Regis and the Dorset coast, which are now held in the Natural History Museum.

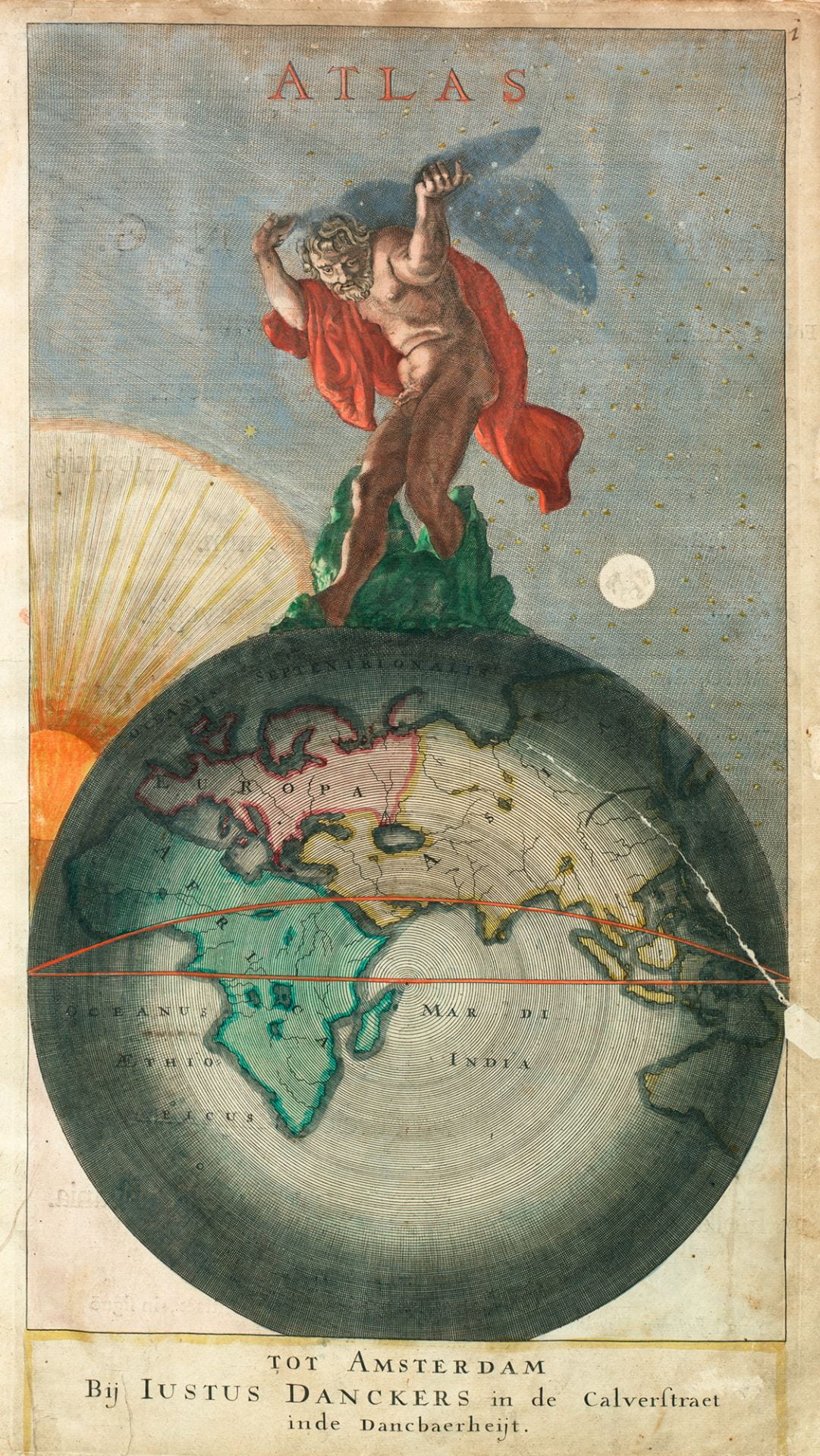

John Martin (1789-1854) was an English Romantic artist, known for his dramatic, apocalyptic scenes. The engraving, The Sea-Dragons as they lived, depicts plesiosaurs attacking an ichthyosaur, while pterosaurs feed on the body of a second ichthyosaur. It forms the frontispiece to The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons by Thomas Hawkins, published in 1840. Thomas Hawkins (1810-1889) was a Somerset fossil collector, who collected fossils from Lyme Regis and the Dorset coast, which are now held in the Natural History Museum. The title page from an atlas of 1690, produced by Justus Danckerts (1635-1701) who was part of a Dutch family of mapmakers, based in Amsterdam. The illustration depicts the titan, Atlas, holding up the sky. Our copy of the atlas came to the University of Bristol Special Collections as part of the Bristol Moravian Church Archive.

The title page from an atlas of 1690, produced by Justus Danckerts (1635-1701) who was part of a Dutch family of mapmakers, based in Amsterdam. The illustration depicts the titan, Atlas, holding up the sky. Our copy of the atlas came to the University of Bristol Special Collections as part of the Bristol Moravian Church Archive.