Ella Pendleton, Project Archivist, reflects on the process of re-cataloguing the Pinney Family Papers and shares examples and themes of the collection

The Pinney Family Papers are among the most used archives in Special Collections, spanning centuries of change from the sixteenth to the twentieth century through the records of one family from Southwest England. The Dorset roots of the family shifted when Azariah Pinney was exiled from England, resulting in his voyage to Nevis in the Leeward Islands. Documents pertaining to the Pinney family’s historic business and properties in the Caribbean, particularly Nevis, exemplify how colonists were able to develop wealth through Caribbean property investments, and through the production of and trade in sugar. However, the enrichment of sugar plantation owners like the Pinneys was built upon human exploitation, enabled through the Transatlantic trafficking of enslaved Africans.

The focus of the project to re-catalogue the Pinney papers, began by Senior Archivist Emma Howgill and picked up by me last September, was conceived in line with decolonial archival practice. This approach seeks to address the imbalance in the historic record and centre the people whose enslavement enabled British colonists to amass wealth, brought profitable trade to port cities like Bristol, and, on a larger scale, provided a foundation for Britain’s economic and industrial development through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

The Caribbean papers of the Pinney family had previously been afforded little structure in the catalogue, but they have now been grouped to reflect aspects of the Pinneys’ activities in the Caribbean. Papers relating to specific estates have been pieced together in subseries based on location and ownership, which help to map the Pinney’s influence and investments across the Caribbean. Further descriptive detail and content notes have also been added to the catalogue to highlight evidence of enslaved people and signpost documents in which racist or other offensive language is used.

Arrival in Nevis

The Pinneys’ pursuit of property and trade in the Caribbean began with Azariah Pinney, who was banished from England following his involvement in the Monmouth Rebellion of 1685. In Nevis, Azariah Pinney began to work as an attorney and manager for established plantation owners. This letter from Mary Travers exemplifies the work conducted by Pinney, whom she gives instructions regarding the management of her Nevis estates; Travers specifies to whom sugar should be shipped and gives Pinney charge of the books and papers of her late husband William Helme.

Letter from Mary Travers (formerly Mary Helme) to Azariah Pinney as her attorney (DM58/2/1/1/48).

Azariah Pinney would eventually become owner of Proctor’s Plantation, in addition to plantations named Charlott’s, Mountain and Lady Bowden’s, which came to form the Pinney’s larger Mountravers estate in St Thomas Lowland, Nevis. The drive for expansion progressed through generations of the family; this volume kept by John Pinney (formerly John Pretor) contains an extensive list of deeds, legal documents and papers related to plantation management, demonstrating the scope of the Pinney’s investments in Caribbean property, grown in part through acting as creditors to indebted estates and their owners.

Volume containing lists of deeds and papers of John Frederick Pinney and lists of people enslaved by John Pinney in Nevis (DM58/2/2/77).

This volume also contains lists of enslaved people, of which there are many in the collection. These lists give an insight into the attitude of the enslavers and their conception of enslaved people as property. They also offer the possibility of researchers tracing individuals through time, giving details of familial relationships and sometimes noting instances of attempts by enslaved people to free themselves from the plantations upon which they were forced to labour.

The life of a sugar plantation

The account books (DM58/3) of the Pinney Papers provide more notes on events and circumstances involving enslaved people, from which small stories can be extracted. One journal (DM58/3/29), which documents daily incoming and outgoing payments, includes a memorandum of 24 March 1781 which describes the escapes of enslaved people named ‘Polydore’ and ‘Charge’, with Polydore thought to have ‘gone on board the Hornet Privateer’. It is possible that this was the Hornet involved in the British raid of Essequibo and Demerara (now part of Guyana) which took place between 24-27 February 1781, shortly before Polydore’s escape. If Polydore did indeed board the Hornet, the length and nature of his voyage, in addition to his status in the ship’s crew, is unclear. This ship, captained by John Kimber, returned to its home port of Bristol in July 1781, and would later engage in raids on merchant ships, while Kimber took command of a ship trafficking enslaved people.

![A journal for Nevis business under John [Pretor] Pinney, containing a memorandum dated 24 March 1781 (Page 17 of DM58/3/29).](https://specialcollections.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2025/11/DM58-3-29-003.jpg)

A journal for Nevis business under John [Pretor] Pinney, containing a memorandum dated 24 March 1781 (Page 17 of DM58/3/29).

![Letter to John Hayne, dated 14 June 1777, in DM58/4/4, a letter book containing copies of the correspondence of John [Pretor] Pinney (DM58/4/4/146).](https://specialcollections.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2025/11/DM58-4-4-146.jpg)

Letter to John Hayne, dated 14 June 1777, in DM58/4/4, a letter book containing copies of the correspondence of John [Pretor] Pinney (DM58/4/4/146).

John Pinney would later depart Nevis, from which point he and his son John Frederick Pinney acted as largely absentee owners, entrusting their Nevis plantations to managers. In 1808, Mountravers was sold by the Pinneys to Edward Huggins, however their stake in Caribbean property remained long after. The family also continued to engage in trade with the Caribbean through business partnerships with the Tobin, Ames and Case families.

Some items in the collection given an insight into the impact, or lack thereof, of the abolition of the trade of enslaved people on the fortunes of the Pinney family. Documentation of the Pinneys’ claims and counterclaims to the Office of Commissioners of Compensation demonstrate how they were empowered to claim compensation for freed enslaved people by the Slave Compensation Act of 1837. The envelope pictured below contains material related to Claim 36 for the Golden Rock estate and Claim 97 for the New River estate, Nevis; in both cases, Charles Pinney was a successful awardee. Letters written by Charles Pinney (see DM58/4/52) similarly note his efforts to gain compensation for people enslaved on further estates in Nevis and St Kitts.

Envelope containing material relating to compensation claims under the Slave Compensation Act of 1837 (DM58/2/1/9/20).

Adjudication and Award for Claim No. 97, relating to people formerly enslaved on the New River plantation in Nevis (DM58/2/1/9/20).

Reflections on the project

Re-cataloguing the Pinney Family Papers has given me an insight into the power of archival evidence in conveying the realities of enslaved labour, from which cities like Bristol profited. It is important that the Special Collections catalogue interrogates the content of collections such as the Pinney Papers, which tell the story from the perspective of the enslavers. There is still more work to be done to address insensitive and offensive language in our catalogue, and to re-evaluate descriptions which may perpetuate colonialist narratives. I hope that the work on the Pinney Papers over the past two years has provided a foundation for these aims, which will continue to be a focus of Special Collections.

![Illustrated page from the ‘Ave Beppo scrapbook’ [c1903] created by Margaret Vaughan [née Symonds], the daughter of John Addington Symonds (DM3271/9/1/3/1).](https://specialcollections.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2025/06/DM3271-9-1-3-1-001.jpg)

![Portrait photograph of John Addington Symonds from an album of photographs, sketches and cuttings [c1894] created by Margaret Symonds (DM3271/10/1/4/1).](https://specialcollections.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2025/06/DM3271-10-1-4-1-001.jpg)

![The pros and cons of living in Davos and Egypt [c1876] (DM3271/7/2/2 ).](https://specialcollections.blogs.bristol.ac.uk/files/2025/06/DM3271-7-2-2-001.jpg)

Special Collections at the University of Bristol holds the largest and longest established collection of election addresses (over 30,000) and campaign literature, from all British parliamentary elections since 1892. We also hold leaflets from London County Council and European parliamentary elections, along with campaign literature from other important national plebiscites such as the 1975 and 2016 referendums on membership of the European Union. This material is available for consultation by students, researchers, journalists, and members of the public.

Special Collections at the University of Bristol holds the largest and longest established collection of election addresses (over 30,000) and campaign literature, from all British parliamentary elections since 1892. We also hold leaflets from London County Council and European parliamentary elections, along with campaign literature from other important national plebiscites such as the 1975 and 2016 referendums on membership of the European Union. This material is available for consultation by students, researchers, journalists, and members of the public. A description of our political collections, including our election address archive, can be found at:

A description of our political collections, including our election address archive, can be found at:

This kaleidoscope mechanical chromotrope magic lantern slide for children dates from around 1870-1880. The slide has two panels and was designed to be inserted into a lantern slide viewer. The handle of the viewer would be turned, so that one panel would move while the other remained stationary, giving a kaleidoscope effect. The slide comes from a collection donated to us by Paul Raphael in February 2023.

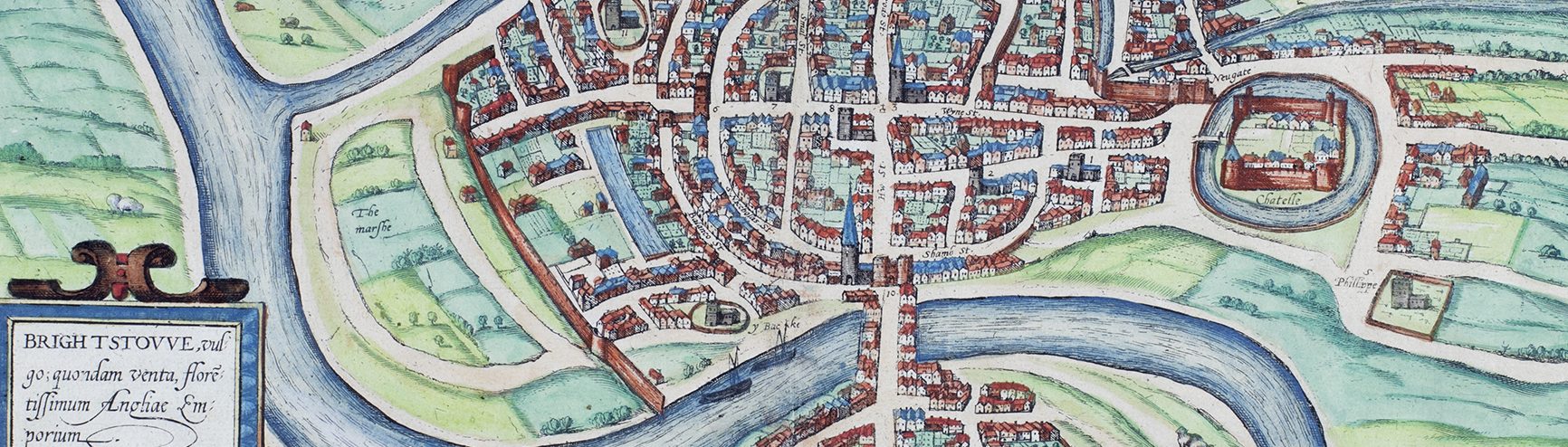

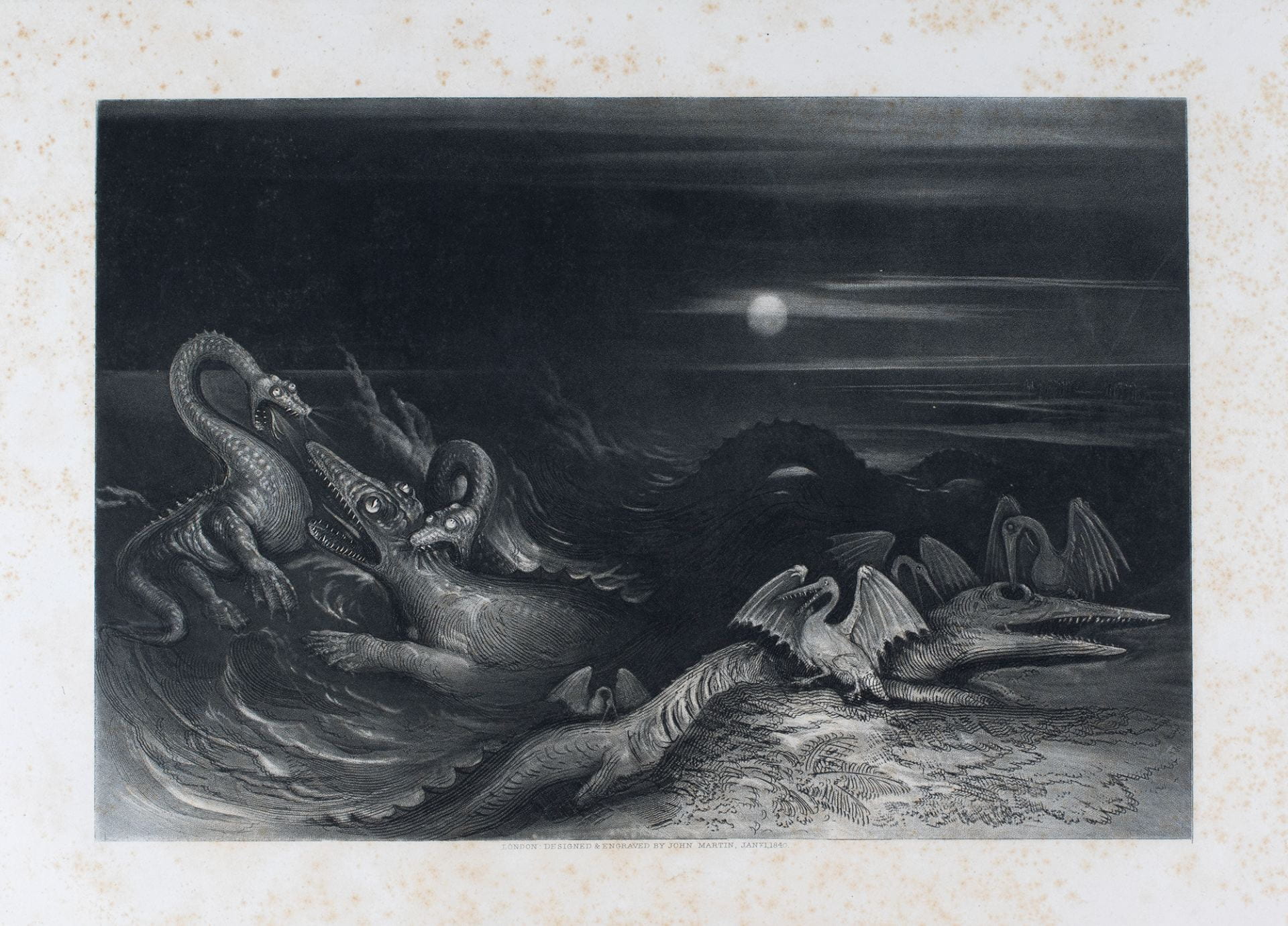

This kaleidoscope mechanical chromotrope magic lantern slide for children dates from around 1870-1880. The slide has two panels and was designed to be inserted into a lantern slide viewer. The handle of the viewer would be turned, so that one panel would move while the other remained stationary, giving a kaleidoscope effect. The slide comes from a collection donated to us by Paul Raphael in February 2023. John Martin (1789-1854) was an English Romantic artist, known for his dramatic, apocalyptic scenes. The engraving, The Sea-Dragons as they lived, depicts plesiosaurs attacking an ichthyosaur, while pterosaurs feed on the body of a second ichthyosaur. It forms the frontispiece to The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons by Thomas Hawkins, published in 1840. Thomas Hawkins (1810-1889) was a Somerset fossil collector, who collected fossils from Lyme Regis and the Dorset coast, which are now held in the Natural History Museum.

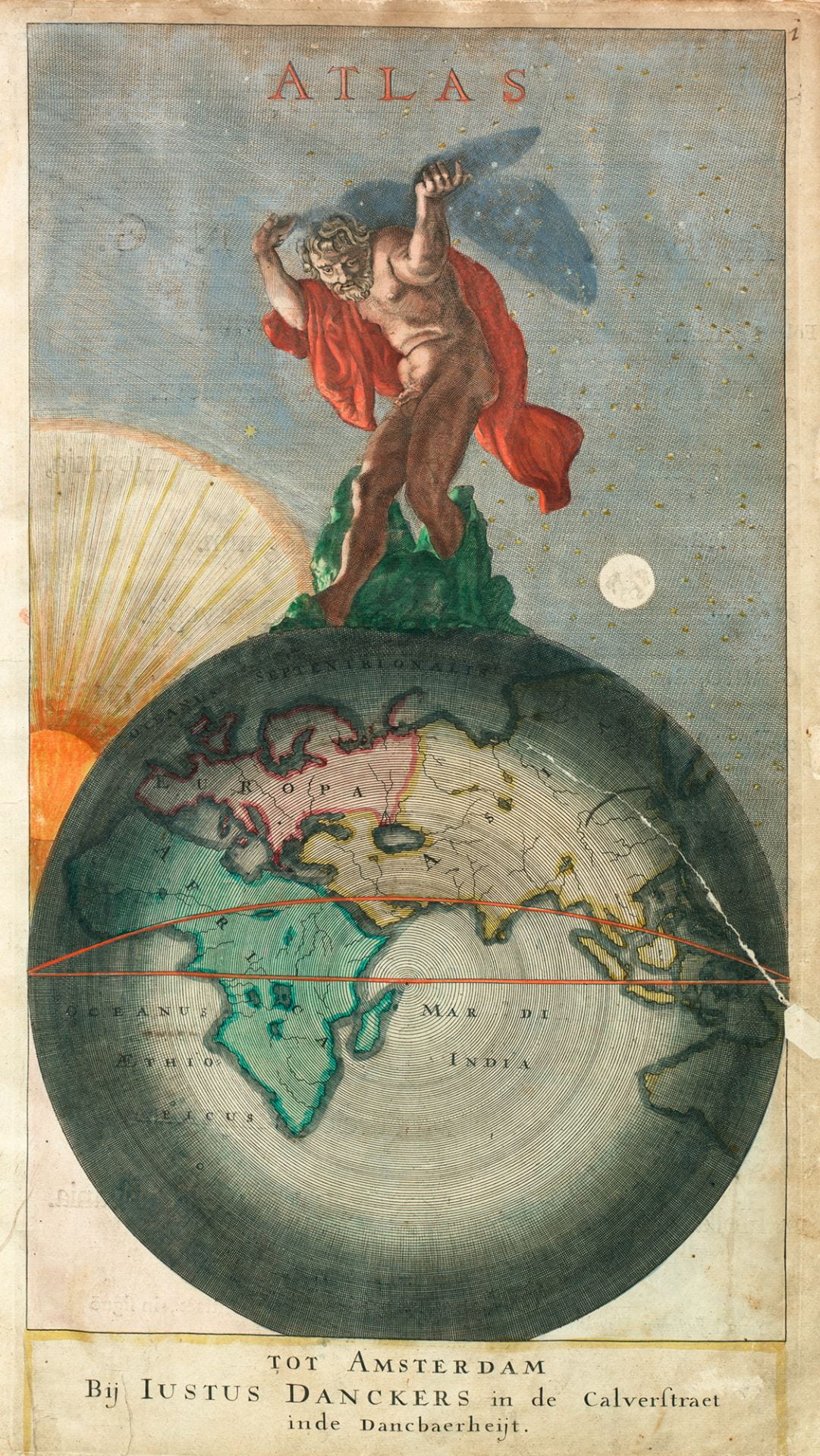

John Martin (1789-1854) was an English Romantic artist, known for his dramatic, apocalyptic scenes. The engraving, The Sea-Dragons as they lived, depicts plesiosaurs attacking an ichthyosaur, while pterosaurs feed on the body of a second ichthyosaur. It forms the frontispiece to The Book of the Great Sea-Dragons by Thomas Hawkins, published in 1840. Thomas Hawkins (1810-1889) was a Somerset fossil collector, who collected fossils from Lyme Regis and the Dorset coast, which are now held in the Natural History Museum. The title page from an atlas of 1690, produced by Justus Danckerts (1635-1701) who was part of a Dutch family of mapmakers, based in Amsterdam. The illustration depicts the titan, Atlas, holding up the sky. Our copy of the atlas came to the University of Bristol Special Collections as part of the Bristol Moravian Church Archive.

The title page from an atlas of 1690, produced by Justus Danckerts (1635-1701) who was part of a Dutch family of mapmakers, based in Amsterdam. The illustration depicts the titan, Atlas, holding up the sky. Our copy of the atlas came to the University of Bristol Special Collections as part of the Bristol Moravian Church Archive.